By Bruce Edmonds

Introduction

Machine-learning systems, including Large Language Models (LLMs), are algorithms trained on large datasets rather than something categorically different. Consequently, they inherit the standard theoretical and practical limitations that apply to all algorithmic methods. Here we look at the computational limits in terms of “Vibe coding” – where the LLM writes some of the code for an Agent-Based Model (ABM) in response to a descriptive prompt. Firstly, we review a couple of fundamental theorems in terms of producing or checking code relative to its descriptive specification. In general, this is shown to be impossible (Edmonds & Bryson 2004). However, this does not rule out the possibility that this could work with simpler classes of code that fall short of full Turing completeness (being able to mimic any conceivable computation). Thus, I recap a result that shows how simple a class of ABMs can be and still be Turing complete (and thus subject to the previous results) (Edmonds 2004). If you do not like discussion of proofs, I suggest you skip to the concluding discussion. More formal versions of the proofs can be found in the Appendix.

Descriptions of Agent-Based Models

When we describe code, the code should be consistent with that description. That is, the code should be one of the possible codes which are right for the code. In this paper we are crucially concerned with the relationship between code and its description and the difficulty of passing from one to the other.

When we describe an ABM, we can do so in a number of different ways. We can do this with different degrees of formality: from chatty natural language to pseudo code to UML diagrams. The more formal the method of description, the less ambiguity there is concerning its meaning. We can also describe what we want at low or high levels. A low-level description specifies the detail of what bit of code does at each time – an imperative description. A high-level description specifies what the system should do as a whole or what the results should be like. These tend to be declarative descriptions.

Whilst a compiler takes a formal, low-level description of code, an LLM takes a high-level, informal description – in the former case the description is very prescriptive with the same description always producing the same code, but in the case of LLMs there are usually a great many sets of code that are consistent with the input prompt. In other words, the LLM makes a great many decisions for the user, saving time – decisions that a programmer would be forced to confront if using a compiler (Keles 2026).

Here, we are focusing on the latter case, when we use an LLM to do some or all of our ABM programming for us. We use high-level, informal natural language in order to direct the LLM as to what ABM (or aspect of ABM) we would like. Of course, one can be more precise in one’s use of language, but it will tend to remain at a fairly high level (if we are going to do a complete low-level description then we might as well write the code ourselves).

In the formal results below, we restrict ourselves to formal descriptions as this is necessary to do any proofs. However, what is true below for formal descriptions is also true for the wider class of any description as one can always use natural language in a precise manner. For a bit more detail in what we mean here by a formal language, see the Appendix.

The impossibility of a general “specification compiler”

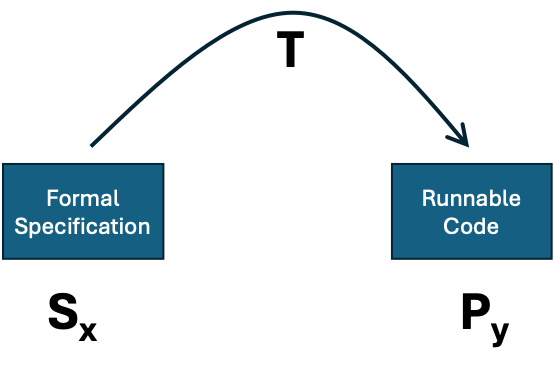

The dream is that one could write a description of what one would like and an algorithm, T, would produce code that fitted that description. However, to enable proofs to be used we need to formalize the situation so that the description, is in some suitably expressive but formal language (e.g. a logic with enumerable expressions). This situation is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Automatically generating code from a specification.

Obviously, it is easy to write an impossible formal specification – one for which no code exists –so the question is whether there could be such an algorithm, T, that would give us code that fitted a specification when it does exist. The proof is taken from (Edmonds & Bryson 2004) and given in more formal detail in the Appendix.

The proof uses a version of Turing’s “halting problem” (Turing 1937). This is the problem of checking some code (which takes a number as an input parameter) to see if would come to a halt (the program finishes) or go on for ever. The question here is whether there is any effective and systematic way of doing this. In other words, whether there an “automatic program checker” is possible – a program, H, which takes two inputs: the program number, x, and a possible input, y and then works out if the computation Px(y) ever ends. Whilst in some cases spotting this is easy – e.g. trivial infinite loops – other cases are hard (e.g. testing the even numbers to find one that is not the sum of two prime numbers1).

For our purposes, let us consider a series of easier problems – what I call “limited halting problems”. This is the problem of checking whether programs, x, applied to inputs y ever come to an end, but only for x, y ≤ n, where n is a fixed upper limit. Imagine a big n ´ n table with the columns being the program numbers and the rows being the inputs. Each element is 0 if the combination never stops and 1 if it does. A series of simpler checking programs, Hn, would just look up the answers in the table as long as they had been filled in correctly. We know that these programs exist, since programs that implement simple look up tables always exist and that one of the possible n x´n tables will be the right one for Hn. For each limited halting problem, we can write a formal specification for this, giving us a series of specifications (one for each n).

Now imagine that we had a general-purpose specification compiling program, T, as described above and illustrated in Figure 1. Then, we could do the following:

- work out max(x,y)

- given any computation Px(y) we could construct the specification for the limited halting problem with index, max(x,y)

- then we could use T to construct some code for Hn and

- use that code to see if Px(y) ever halted.

Taken together, these steps (a-d) can be written as a new piece of computer code that would solve the general halting problem. However, this we know is impossible (Turing 1937), therefore there is not a general compiling program like T above, it is impossible.

The impossibility of a general “code checker”

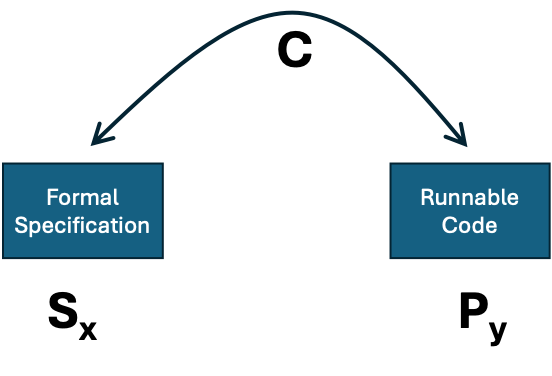

The checking problem is apparently less ambitious than the programming problem – here we are given a program and a specification and have ‘only’ to check whether they correspond. That is whether the code satisfies the specification.

Figure 2. Algorithmically checking if some code satisfies a descriptive specification.

Again, the answer is in the negative. The proof to this is similar. If there were a checking program C that, given a program and a formal specification would tell us whether the program met the specification, we could again solve the general halting problem. We would be able to do this as follows:

- work out the maximum of x and y (call this m);

- construct a sequence of programs implementing all possible finite lookup tables of type: mxm→{0,1};

- test these programs one at a time using C to find one that satisfies SHn (we know there is at least one);

- use this program to compute whether Px(y) halts.

Thus, there is no general specification checking program, like C.

Thus, we can see that there are some, perfectly well-formed specifications, where we know code exists that would comply with the specification but where there is no such algorithm, however clever, that will always take us from a specification to the code. Since trained neural nets are a kind of clever algorithm, they cannot do this either.

What about simple Agent-Based Models?

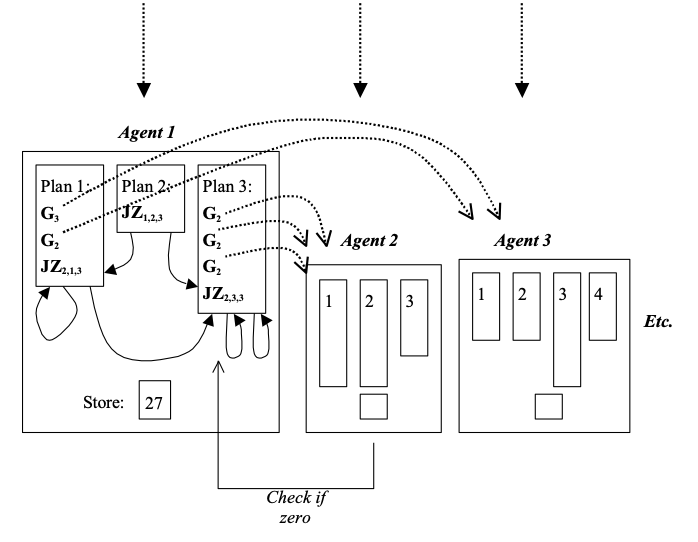

To illustrate how simple such systems can be, I defined a particular class of particularly simple multi-agent system, called “GASP” systems (Giving Agent System with Plans). These are defined as follows. There are n agents, labelled: 1, 2, 3, etc., each of which has an integer store which can change and a finite number of simple plans (which do not change). Each time interval the store of each agent is incremented by one. Each plan is composed of: a (possibly empty) sequence of ‘give instructions’ and finishes with a single ‘test instruction’. Each ‘give instruction’, Ga, has the effect of giving 1 unit to agent a (if the store is non-zero). The ‘test instruction’ is of the form JZa,p,q, which has the effect of jumping (i.e. designating the plan that will be executed next time period) to plan p if the store of agent a is zero and plan q otherwise. This class is described more in (Edmonds 2004). This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. An Illustration of a “GASP” multi-agent system.

Thus ‘all’ that happens in this class of GASP systems is the giving of tokens with value 1 to other agents and the testing of other agents’ store to see if they are zero to determine the next plan. There is no fancy communication, learning or reasoning done by agents. Agents have fixed and very simple plans and only one variable. However, this class of agent can be shown to be Turing Complete. The proof is taken from (Edmonds & Bryson 2004).

The detail of this proof is somewhat tedious, but basically involves showing that any computation (any Turing Machine) can be mapped to a GASP machine using a suitable effective and systematic mapping. This is done in three stages. That is for any particular Turing Machine:

- Create an equivalent “Unlimited Register Machine” (URM), with an indefinitely large (but finite) number of integer variables and four basic kinds of instruction (add one to a variable, set a variable to 0, copy the number in a variable to another, jump to a set instruction if two specified variables are equal. This is known to be possible (Cutland page 57).

- Create an equivalent “AURA” machine for this URM machine (Moss & Edmonds 1994)

- Create an equivalent “GASP” ABM for this AURA system.

This is unsurprising – many systems that allow for an indefinite storage, basic arithmetic operations and a kind of “IF” statement are Turing Complete (see any textbook on computability, e.g. Cutland 1980).

This example of a class of GASP agents shows just how simple an ABM can be and still be Turing Complete, and subject to the impossibility of a general compiler (like T above) or checker (like C above), however clever these might be.

Discussion

What the above results show is that:

- There is no algorithm that will take any formal specification and give you code that satisfies it. This includes trained LLMs.

- There is no algorithm that will take any formal specification and some code and then check whether the code satisfies that specification. This includes trained LLMs.

- Even apparently simple classes of agent-based model are capable of doing any computation and so there will be examples where the above two negative results hold.

These general results do not mean that there are not special cases where programs like T or C are possible (e.g. compilers). However, as we see from the example ABMs above, it does not take much in the way of its abilities to make this impossible for high level descriptions. Using informal, rather than formal, language does not escape these results, but merely adds more complication (such as vagueness).

In conclusion, this means that there will be kinds of ABMs for which no algorithm can turn descriptions into the correct, working code2. This does not mean that LLMs can’t be very good at producing working code from the prompts given to them. They might (in some cases) be better than the best humans at this but they can never be perfect. There will always be specifications where they either cannot produce the code or produce the wrong code.

The underlying problem is that coding is a very hard, in general. There are no practical, universal methods that always work – even when it is known to be possible. Suitably-trained LLMs, human ingenuity, various methodologies can help but none will be a panacea.

Notes

1. Which would disprove “Goldbach’s conjecture”, whose status is still unknown despite centuries of mathematical effort. If there is such a number it is known to be more than 4×1017.

2. Of course, if humans are limited to effective procedures – ones that could be formally written down as a program (which seems likely) – then humans are similarly limited.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks for the very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this by Peer-Olaf Siebers, Luis Izquierdo and other members of the LLM4ABM SIG. Also, the participants of AAMAS 2004 for their support and discussion on the formal results when they were originally presented.

Appendix

Formal descriptions

The above proofs rely on the fact that the descriptions are “recursively enumerable”, as in the construction of Gödel (1931). That is, one can index the descriptions (1, 2, 3…) in such a way that once can reconstruct the description from the index. Most formal languages, including those compilers take, computer code, formal logic expressions, are recursively enumerable since they can be constructed from an enumerable set of atoms (e.g. variable names) using a finite number of formal composition rules (e.g. if A and B are allowed expressions, then so are A → B, A & B etc. Any language that can be specified using syntax diagrams (e.g. using Backus–Naur form) will be recursively enumerable in this sense.

Producing code from a specification

The ‘halting problem’ is an undecidable problem (Turing 1937), (that is it is a question for which there does not exist a program that will answer it, say outputting 1 for yes and 0 for no). This is the problem of whether a given program will eventually come to a halt with a given input. In other words, whether Px(y), program number x applied to input y, ever finishes with a result or whether it goes on for ever. Turing proved that there is no such program (Turing 1937).

Define a series of problems, LH1, LH2, etc., which we call ‘limited halting problems’. LHn is the problem of ‘whether a program with number £n and an input £n will ever halt’. The crucial fact is that each of these is computable, since each can be implemented as a finite lookup table. Call the programs that implement these lookup tables: PH1, PH2, etc. respectively. Now if the specification language can specify each such program, one can form a corresponding enumeration of formal specifications: SH1, SH2,etc.

The question now is whether there is any way of computationally finding PHn from the specification SHn. But if there were such a way we could solve Turing’s general halting problem in the following manner: first find the maximum of x and y (call this m); then compute PHm from SHm; and finally use PHm to compute whether Px(y) halts. Since we know the general halting problem is not computable, we also know that there is no effective way of discovering PHn from SHn even though for each SHn we know an appropriate PHn exists!

Thus, the only question left is whether the specification language is sufficiently expressive to enable SH1, SH2, etc. to be formulated. Unfortunately, the construction in Gödel’s famous incompleteness proof (Gödel 1931) guarantees that any formal language that can express even basic arithmetic properties will be able to formulate such specifications.

Checking code meets a specification

To demonstrate this, we can reuse the limited halting problems defined in the last subsection. The counter-example is whether one can computationally check (using C) that a given program P meets the specification SHn. In this case we will limit ourselves to programs, P, that implement n´n finite lookup tables with entries: {0,1}.

Now we can see that if there were a checking program C that, given a program and a formal specification would tell us whether the program met the specification, we could again solve the general halting problem. We would be able to do this as follows: first find the maximum of x and y (call this m); then construct a sequence of programs implementing all possible finite lookup tables of type: mxm→{0,1}; then test these programs one at a time using C to find one that satisfies SHn (we know there is at least one: PHm);and finally use this program to compute whether Px(y) halts. Thus, there is no such program, C.

Showing GASP ABMs are Turning Complete

The class of Turing machines is computationally equivalent to that of unlimited register machines (URMs) (Cutland page 57). That is the class of programs with 4 types of instructions which refer to registers, R1, R2, etc. which hold positive integers. The instruction types are: Sn, increment register Rn by one; Zn, set register Rn to 0; Cn,m, copy the number from Rn to Rm (erasing the previous value); and Jn,m,q, if Rn=Rm jump to instruction number q. This is equivalent to the class of AURA programs which just have two types of instruction: Sn, increment register Rn by one; and DJZn,q, decrement Rn if this is non-zero then if the result is zero jump to instruction step q (Moss & Edmonds 1994). Thus we only need to prove that given any AURA program we can simulate its effect with a suitable GASP system. Given an AURA program of m instructions: i1, i2,…, im which refers to registers R1, …, Rn, we construct a GASP system with n+2 agents, each of which has m plans. Agent An+1 is basically a dump for discarded tokens and agent An+2 remains zero (it has the single plan: (Gn+1, Ja+1,1,1)). Plan s (sÎ{1,…,m}) in agent number a (aÎ{1,…,n}) is determined as follows: there are four cases depending on the nature of instruction number s:

1. is is Sa: plan s is (Ja,s+1,s+1);

2. is is Sb where b¹a: plan s is (Gn+1, Ja,s+1,s+1);

3. is is DJZa,q: plan s is (Gn+1, Gn+1, Ja,q,s+1);

4. is is DJZb,q where b¹a: plan s is (Gn+1, Ja,q,s+1).

Thus, each plan s in each agent mimics the effect of instruction s in the AURA program with respect to the particular register that the agent corresponds to.

References

Cutland, N. (1980) Computability: An Introduction to Recursive Function Theory. Oxford University Press.

Edmonds, B. (2004) Using the Experimental Method to Produce Reliable Self-Organised Systems. In Brueckner, S. et al. (eds.) Engineering Self Organising Sytems: Methodologies and Applications, Springer, Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence, 3464:84-99. http://cfpm.org/cpmrep131.html

Edmonds, B. & Bryson, J. (2004) The Insufficiency of Formal Design Methods – the necessity of an experimental approach for the understanding and control of complex MAS. In Jennings, N. R. et al. (eds.) Proceedings of the 3rd Internation Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents & Multi Agent Systems (AAMAS’04), July 19-23, 2004, New York. ACM Press, 938-945. http://cfpm.org/cpmrep128.html

Gödel, K. (1931), Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme, I, Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik, 38(1):173–198. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF01700692

Keles, A. (2026) LLMs could be, but shouldn’t be compilers. Online https://alperenkeles.com/posts/llms-could-be-but-shouldnt-be-compilers/ (viewed 11 Feb 2026)

Moss, S. and Edmonds, B. (1994) Economic Methodology and Computability: Some Implications for Economic Modelling, IFAC Conf. on Computational Economics, Amsterdam, 1994. http://cfpm.org/cpmrep01.html

Turing, A.M. (1937), On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, s2-42: 230-265. https://doi.org/10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230

Edmonds, B. (2026) A Reminder – computability limits on “vibe coding” ABMs (using LLMS to do the programming for us). Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 12 Feb 2026. https://rofasss.org/2026/02/12/vibe

© The authors under the Creative Commons’ Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND) Licence (v4.0)