*Corresponding author, 1Information Technology, Wageningen, 2Department of Computer Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 3School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo, 4Institut für Umweltsystemforschung, Universität Osnabrück, 5Potsdam University of Applied Sciences

Table of Contents

Approach

Ambition

With this position paper the authors posit the need for a research area of Artificial Sociality. In brief this means “computational models of the essentials of human social behaviour”; we shall elaborate below. The need for artificial sociality is justified by the encroachment of simulations and knowledge technology, including Artificial Intelligence (AI), into the fabric of our societies. This includes smart devices, biosensors, facial recognition, coordination apps, surveillance apps, search engines, home and care robots, social media, machine learning modules, and agent-based simulation models of socio-ecological and socio-economic systems. It will include many more invasive technologies that will be invented in the coming decades. Artificial sociality is a way to connect human drives and emotions to the challenges our societies face, and the management and policy actions we need to take. In contrast to mainstream AI research, artificial sociality targets the social embeddedness of human behaviour and experience; we could say the collective intelligence of human societies rather than the individual intelligence of single agents. Human sociality has characteristics that differ from other varieties of sociality, while having variation across cultures (Henrich, 2016). In this piece, we concentrate on the incorporation of human sociality into agent-based computational social simulation models as a testbed for the integration of the various elements of artificial sociality.

The issue of artificial sociality is not new, as we’ll discuss below in the “State of the art” section. Our evolutionary perspective, we feel, offers new possibilities for integrating various strands of research. Our ambition is mainly to find a robust ontology for artificial human sociality, rooted in our actual evolutionary history and allowing to distinguish cultures. We hope that efforts at engineering computational agents and societies can benefit from this work.

Why is sociality so important?

Humans are eusocial

Sociality is a word used across various sciences. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio makes it a central concept, arguing that it is present in all social creatures, even long predating multicellular organisms (Damasio, 2018). In agreement with Wilson & Holldöbler (Edward O. Wilson & Hölldobler, 2005), Wikipedia defines it in a biological way: “Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies”. The site continues: “The highest degree of sociality recognized by sociobiologists is eusociality. A eusocial taxon is one that exhibits overlapping adult generations, reproductive division of labor, cooperative care of young, (…).” Obviously, this definition holds for humans. We are a eusocial primate species.

Why are we in the world?

A grand question in philosophy is “Why are we in the world?”. Evolutionary biology would answer “because our ancestors reproduced, ever since the beginnings of life”. The next question is “Why did our ancestors reproduce?” Well, they did so because “they were fit, and conquered natural and human-made hazards”. Thirdly, “Why were they fit?” This third “why” question takes us to sociality. Being eusocial gave our ancestors the fitness they needed. It allowed them to cooperate and divide tasks in groups. Millions of years ago, early hominins gathered, hunted, defended themselves, cared for the weak, exchanged goods and foods (G. Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010), chapter 12.

Sociality integrates elements of all possible sciences that are useful in comprehensively modelling human (or non-human) social behaviour, drives, and decision making. It spans from the “what” to the “why” to the “how”. The notion of sociality changes the meaning of the concept of intelligence into something that could be group-level, not individual-level. The most astounding fact about humans is the high degree of social or collective intelligence. Because of the protection it affords, collective intelligence even raises the tolerance for individual ineptness (Diamond, 1999).

Artificial sociality

Artificial sociality is the study of sociality by means of computational modelling. This could take many forms, e.g. social robotics, body-worn devices. In this paper we focus on computational social simulation with a particular focus on sociality. The application to computational social simulation sets purpose and limits to the selection of potentially relevant knowledge. Artificial sociality will be concerned with building blocks and primitives that are chosen so as to be reusable for a multitude of applications. In this sense it is a transformative endeavour. It offers a systematic integration of the existing insulated approaches sponsored by diverse disciplines to understand and analyse the human condition in all its facets. The primitives developed for artificial sociality should have the potential to be used by a great many applied scholars. More importantly, the dedicated integrated treatment of disciplines is increasingly recognised as necessary to produce sufficiently accurate insights, such as the impact of cultural aspects on the assessment of social policy outcomes (Diallo, Shults, & Wildman, 2020). Applications that benefit from a systematic consideration of artificial sociality include models of human collective action in society, in socio-environmental, socio-economical, or socio-technical systems. Typically, these models would be used to support policy making by achieving a better understanding of the dynamics of target systems.

The history of sociality

Early hominins were mentioned above. In the evolution of life, sociality is actually much older than that. To properly appreciate its importance, we’ll present a brief history of sociality.

Sociality is as old as slime moulds, primitive organisms (“Protista”) that are usually monocellular (e.g. Dictyostelium). Slime moulds know collective action and large-scale division of labour. Social insects such as bees and ants are a more familiar case of successful sociality. Among mammals, there are the burrowing mole rats who live in eusocial colonies. These, or similar, life forms are linked to us by an unbroken chain of life. Sociality has an ancient path dependency.

Hominins

Limiting ourselves to the last million years, our hominin ancestors have brought sociality to a new level. In contrast to other primates, humans have not radiated into distinct species, but merged into one genetically closely related pool, with tremendous cultural variation. They did this through a combination of migrating, fighting, spreading of diseases, cross-breeding, and massive copying of inventions. Some of the latter are mastery of fire, language, script, law, agriculture, religion, weapons and money. Our present-day sociality is the outcome of an unbroken chain of reproduction, all the way since the origins of life until today. At present, fission-fusion dynamics happen all the time in all human societies. Divisions between groups of people are deeply gut-felt. They range from stable across generations to ephemeral; but they are not genetically deep, nor absolute. Yet they matter greatly for the behaviour of our policy-relevant systems. Religions, political alliances, trade networks, but also social media hypes and terrorist movements are cases in point.

Victims of reason

In recent centuries, humans have tended to forget that for all our cleverness and symbolic intelligence, humans are also still social mammals with deep relational drives. Our relational drives tell our intelligence what to do, and do so generally without being transparent to us (Haidt, 2012; Kahneman, 2011). A purely cognitive or rational paradigm cannot capture all of these drives. Thus, when trying to understand our collective behaviours, we can be “victims of reason”. To quote Montesquieu: “Le Coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît point” (‘the heart has its reasons unknown to reason’) (Montesquieu, 1979 [1742]). Artificial sociality goes beyond reason, identifying the unknowns of underlying relational motives. Yes, expected profit is an important motive; but it is relational profit that matters, influenced by gut feelings and emotions such as love, hate, pride, shame, envy, loyalties. Financial profit for the individual is just a special case. As theorized eloquently by Mercier and Sperber (Mercier & Sperber, 2017), reason is used by humans for social acceptance far more than it is used for accuracy. Basically, reason is used for arguing and justifying a position in a social group to enhance influence on, and acceptance by, the group.

Watch the lake, not just the ripples

When we create policy, we tend to run from incident to incident, often forgetting to consider the patterns of path dependence linking these incidents. Causal chains of things happening today run backwards into deep history. The French revolution for instance, while seemingly showing limited impact on life nowadays, has changed and shaped the conception of the nation state and of rights that modern citizens comfortably assume to be omnipresent. Similarly, present-day individualism can be traced back to the marriage policies of the medieval catholic church (Henrich, 2020). For both these examples, it stands to reason that even older sources exist, hidden on the unbroken path of history. Across undoubted and transformative change, there is a continuity to history, especially where sociality is concerned. Sociality is about understanding the lake of human nature, in order to better anticipate the ripples on it.

Why artificial sociality?

Fully understanding sociality is vital for our survival. Artificial sociality, by showing sociality in action, can help. Here we propose a list of principles that indicate how vital it is to understand sociality better. Therefore, they justify developing artificial sociality.

- Systems over disciplines – The earth in the Anthropocene is one system, of which key aspects are ecology, economy, and technology. All of these are known by our intellect. Their development is driven by our sociality. To understand these systems, including human sociality, we need to integrate knowledge across disciplines. This includes both natural and social sciences.

- Multi-level systems – Grand challenges are multi-level. They are about water, climate, contagious diseases, migration, peace. They involve people and groups in systems combined of natural, institutional and economic subsystems. They have dynamics and feedback cycles, often leading to unanticipated and undesired outcomes. They may or may not be subject to policy, but they are unavoidably subject to sociality.

- Emotions AND Rationality – In disciplines concerned with modelling human behaviour, there is a tendency to work on the assumption that “we are our brains” (Swaab & Hedley-Prole, 2014). A broad cross-disciplinary perspective, as well as life experience, make it clear that this is not really the case. Sociality has reason for breakfast: we are subject to gut feelings, we are driven, or get carried away, by emotions. Artificial sociality can bring these things to life.

- Interaction over Individuals – The behaviour of our systems strongly hinges on the sociality of the people in them. Key issues have to do with gut feelings, emotions, trust, communication, hierarchy, group affiliation, power, politics, geopolitics. All of these rest not in the individual but emerge from social interactions

- Explainability over black boxes – While data-driven modelling experiences great popularity, models purely based on data render limited insight into the conceptual inner workings of a social system and its meaning for a target system (i.e., the social reality it represents). Artificial sociality needs to seek a balance of theory, data, and understanding. Analysing policy without understanding interaction effects limits scientific and practical value.

For whom?

- Interdisciplinary researchers can use artificial sociality in models for understanding their target systems.

- Policy makers can create better ideas and policies if they are helped by plausible systemic models of the issues they face and the dynamics those issues exhibit.

- Citizens can act as policy makers, taking their fate into their hands.

- Designers of intelligent systems can integrate knowledge about social dynamics.

With whom?

- All disciplines in the social and life sciences. In order to articulate artificial sociality, all disciplines that study human life can potentially contribute. This ranges across levels of integration: anthropology, artificial intelligence, behavioural biology, behavioural economics, cultural psychology, evolutionary biology, history, neurosciences, psychology, small group behaviour, social geography, social psychology, sociology, system biology…the spirit is one of consilience (Edward O Wilson, 1999).

- Non-academic stakeholders (e.g., governments, the general public). Not only can participatory approaches help uncover hidden rules and drivers of behaviour, but also can artificial sociality be an educational tool for an enlightened society to raise its self-reflection and awareness of its inner workings.

How?

- We recognize the integration of various disciplines’ involvements, the diversity of their respective data, theories, concepts and methods, as a challenging endeavour. In many instances we are struck by gaps between involved disciplines, and the ability to integrate data and theory in a systematic manner. Just because one theory is right does not mean that another one is wrong; often, there is complementarity, if one is willing to search for it.

- Simulation and levels of abstraction. To this end, simulation offers the necessary capabilities, since its approach has the potential to traverse disciplines by offering broad accessibility, modelling at abstraction levels that correspond to the analytical levels within different disciplines (e.g., micro, meso and macro level in sociological research). Its unique ability to afford the systematic integration of theory and data (Tolk, 2015), deductive and inductive reasoning has rendered social simulation as a “third way of doing science” (R. Axelrod, 1997), while available computational resources allow us to explore artificial sociality at scale.

- Creative spark. Computational simulation requires a design effort that links its various contributions into mechanisms. These constitute an original, interdisciplinary contribution. They can themselves be validated.

- Disciplinary contributions. Social simulation is conceptually a method embedded in life sciences, complexity, and social-scientific disciplines. Each of our models creates a miniature world. These worlds need all kinds of input from various sources and disciplines.

- Practicable outputs. Agent-based social simulation typically intends to produce practicable outputs, using theory, data and intuitions as its inputs regardless of their origin (Tolk, 2015) (Edmonds & Moss, 2005). Therefore, social simulation, in particular agent-based modelling, and artificial sociality, should institutionally be fed by many disciplines. All researchers from all disciplines are welcome.

- Dynamics. Agent-based models are eminently suitable to help understand the dynamics of systems. They allow one to investigate unintended collective patterns arising from individual motives, intra- and intergroup dynamics. In other words, they can link disciplines at different levels of aggregation, from the individual to the society. Sensitivity analysis of these dynamics is an integral part of the method.

State of the art on sociality across disciplines

Research into human behaviour has been carried out for a long time, and in many disciplines. Such research, usable or even intended for modelling, has been picking up in recent decades. It would be presumptuous to try and give a full review of developments. Yet we believe that it is useful to give a brief overview of what is happening in various disciplines. To avoid distracting from our purpose, the details are in the appendix.

What we need from the disciplines

Given our position that every living thing that exists today, has evolved and continues to evolve, we need contributions of various types for making sense of sociality. Let us, for one moment, consider life as a game of chess. In such a model, we need to know the what, the why and the how. In our proposal, these elements will become intertwined.

- What: the constitutive elements (chessboard, pieces); the starting position, the rules of the game (formal and etiquette).

- Why: the motivation of the players during a game: typically, this would be “capturing the enemy king”, but other motives could occur. For instance, I might want to lose, for motivating a junior opponent, or win, for challenging him or her.

- How: the configurations that are meaningful, and sequences of moves that can make these configurations happen. Limitations in players’ skills can reduce the space of possibilities.

These questions also obtain for sociality:

- What: medical- and neurosciences study our constitutive elements. History, institutional economics and anthropology study what collective behaviours occur in groups of people.

- Why: evolutionary biology studies the origins of sociality. Psychology studies human motivation today, for instance in leadership, organizational behaviour, clinical -, social- and cultural psychology. Ethology does the same for non-human creatures.

- How: Sociology tends to describe the how of sociality, for instance patterns, their causes and their sequences. Computational branches in biology, economics, and sociology construct artificial worlds. Simulation gaming, and experimental economics do the same with real people, in artificial incentive structures.

For computational modelling we will need input on all three of these questions. The models will require

- A “what”: agents in an environment.

- A “why”: motivation for the agents: drives, urges, goals.

- A “how”: perceptions and actions for the agents, and coordination of these across space and time. This will lead to emergent pattern.

The three questions are really highly intertwined; we take them apart only for the sake of exposition. Also, the emergent pattern of one branch of science, or of a simulation model, can become the input, taken as given, of another. For instance, some models could investigate the emergence of institutions, norms, or culture; others could use such concepts as input variables.

The take-home message of this section is that our modelling efforts will be best served by an eclectic mode that draws from a broad variety of sciences.

What the disciplines tell us

We shall now attempt a synthesis of work on sociality across disciplines presented in the appendix that are important for the research agenda of artificial sociality. To structure it, we stick to our what, why and how questions. Admittedly, our synthesis is partial; this is done for the sake of purposefulness, not because other perspectives could not have merit.

What

Sociality is not a human invention. It is absolutely central to life on earth, and has been since billions of years, in an unbroken chain of reproduction. Sociality has served to preserve homeostasis in populations, enabling some to reproduce (Damasio, 2018). It is as old as monocellular organisms, many of which are known to coordinate their behaviours in response to external stimuli, particularly at the service of reproduction. Human sociality is special in a few ways (Henrich, 2016). We coordinate in many ways with many people we do not personally know. For achieving joint action, we have basically two mechanisms. In evolutionary terms these are prestige and dominance (Henrich, 2016). In sociological terms: status and power (Theodore D. Kemper, 2017). Also, groups of followers are able to curtail the power of leaders. For these functions we evolved intense emotional lives (J. E. Turner, 2007). Emotions are the proximate indicators of our sociality that our organisms provide to us. We’ll return to these issues under “how”.

Selective pressures do not just operate between individuals, but at many levels. There is selective pressure between individuals, human groups, forms of coordination, even ideas. Models can concentrate on any of these levels.

Why

Sociality, in terms of status and power motives in multiple, changing groups, and attending feelings and emotions, is necessary for solving coordination problems, e.g. dividing food, reproducing, bringing up children, or avoiding traffic congestion; and for solving collective action problems and social dilemmas, e.g. selecting a leader, disposing of a dysfunctional leader, or distributing resources across the citizens of a country. This holds in small groups and families with informal social bonds as well as in large groups or societies that rely on formal, depersonalised interaction patterns. Without sociality there can be neither Gemeinschaft (community) nor Gesellschaft (society). Sociality shapes our moral sense.

How

In Humans, sociality develops very early in life, preceding speech and walking. It requires intense care, play, and education during many years; we are a neotenous species, remaining juvenile for many years and even keeping some brain plasticity during adult life. For a baby, the organism has precedence. After just a few months, giving and conferring status becomes important. Between 11 and 19 months, power use develops (Eliot, 2009). During childhood, the social world grows, and various reference groups become distinguished. We learn the dynamics of prestige / status giving and claiming. At puberty, sociality more or less plateaus; just like we speak with the accent of our childhood, we act with its culture. Our hormonal systems are aligned with the dual nature of prestige / status and dominance / power; more on this in the appendix.

This phenomenon of a flexible beginning then stable existence also holds for groups of people. Once formed, societies, groups, organizations and companies, have cultures that tend to remain stable over time, despite many perturbations (Beugelsdijk & Welzel, 2018; G. Hofstede et al., 2010).

Sociality happens. Every action in which several people are present or imagined provides an instance to mutually imprint sociality through status-power dynamics in a world of groups. This ranges from glances and nonverbal involuntary movements, to explicit verbal communication, to social media posts and likes, to elaborate rituals involving prestige and social roles, to coercive acts involving life and death. All of these constitute as many claims for, and accord or refusals of, status; and some of them include power moves.

Groups in society are endlessly variable. They change at various timescales, from life-long to context-dependent and ephemeral. They can be nested or overlapping. Their salience is socially and situationally determined.

Collective results of social acts need not be intended. Much of our societies’ behaviour largely emerges unplanned. A few frequent, archetypical patterns can often be seen in this unplanned system-level behaviour. Agent-based modelling is privileged as a method by allowing to generate these unplanned patterns.

Key theories

There is such a wealth of theoretical work in so many disciplines that even the brief overview above may seem a bit unorganized. Therefore we briefly mention a few of the theories that we’ll most use in our proposal.

- Kemper’s status – power – reference-group theory of relations. This comprehensive sociological theory also touches on neurobiology and psychology. This makes it compatible with evolutionary theories of human sociality. The appendix has a more elaborate treatment.

- Heise’s Affect Control Theory (ACT). This theory shares a lot of elements with Kemper’s status – power dynamics but is targeted to small group interactions.

- Tajfel & Turner’s Social Identity Approach (SIA). This theory elaborates on elements of group and intergroup dynamics, somewhat similar to Kemper’s reference groups.

Work to do in artificial sociality

The synthesis above suggests that sociality is about things that we do, and things that happen between people, in any of the contexts of their lives. Artificial sociality can reproduce sociality using modelling techniques that make life happen: “generative social science” (Epstein, 2006), or, with a newer word, computational social simulation. The task for artificial sociality is first and foremost a modelling task with the ambition to understand sociality-in-action better.

Principles

Ontologically, our perspective is one of consilience. Since there is only one world, findings that align across different sciences are particularly interesting to use in models of sociality. This is the case with the match between neurobiology, emotions, and the status-power theory of relations discussed in the appendix, for example.

Vocabulary

One of our tasks is to generate better understanding and a common vocabulary. At present, many modellers criss-cross the same conceptual space, but with different maps from different reference disciplines.

Open world hypothesis

In order to be able to talk with one another and build shared vocabulary, researchers should maintain an open world hypothesis: if your model differs from mine, then we can talk. What is the difference, is it really a difference, what does that allow or disable? Such discussion allows us to enrich our ontology. It is unrealistic, anyway, to expect everyone to agree. Artificial sociality is heavily loaded with worldview, and people disagree on worldviews. This is actually something that artificial society should help explain; unfortunately, we can predict that such an explanation will not please everyone.

Realms to model

Our sociality operates in a world with non-social elements such as space, time, objects. On a scale from content-based to relational, we can distinguish four realms that need to be modelled.

- This means the bio-physical and the institutional world, divorced from what people might feel about it.

- Cognitions about content. This includes knowledge, opinions, norms, and values that influences our perspectives on the content realm. They are partially conscious, the less so the more they are shared (and therefore cultural). This realm binds the relational to the non-relational world.

- Cognitions about relations. We have ideas about the status (“social importance”) and power that others have, about our own status and power in groups. These are normally unconscious.

- Cognitions about our own organism. This includes all kinds of organismic feelings, again often not fully conscious, and may include meta cognitions (e.g. “thinking about thinking”). Emotions link the organism with the relational world, often unconsciously. For instance, an insult is an attack on our status, and may bring the blood to our cheeks.

Artificial sociality requires considering all these elements. To which extent we consider each of them can be case-dependent. Depending on the application, some might have to be further elaborated. It is possible to model only one or several of these realms. For instance, Kemper’s theory posits the organism as one of the relevant reference groups, merging 3. and 4. Hofstede’s GRASP world has only sociality (3.) and no content (Gert Jan Hofstede & Liu, 2020). The general-purpose link from emotion as coherent dynamic social meaning, to content as objects and actions in institutional frames proposed in BayesACT may provide a link between (1.), (2.) and (3.) (Schröder, Hoey, & Rogers, 2016). Ultimately all of the realms will be needed in combination.

Theories and realms

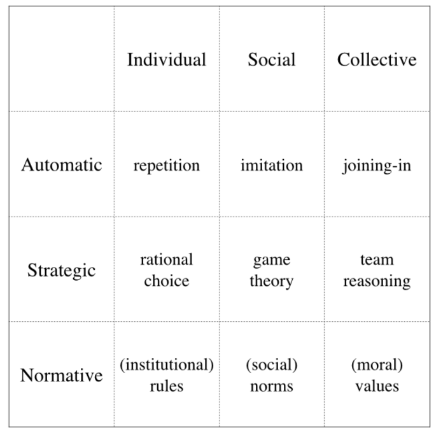

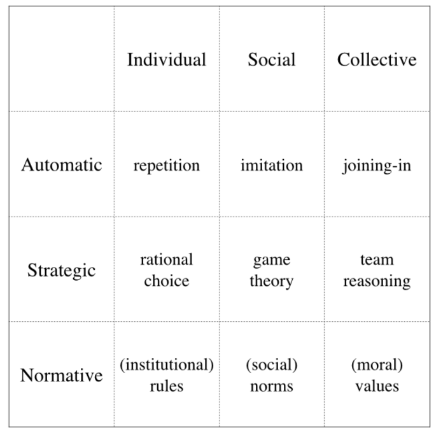

Theories from the social sciences tend to concentrate on a subset of these realms. Table 1 indicates this.

Table 1: theories and realms to model (legend: from – not included, … to +++ central to this theory)

| Theory |

modelled realms |

| |

Content |

Cognitions |

| |

|

on content |

on relations |

on organism |

| Affect Control Theory (Heise, 2013) |

– |

+ |

++ |

|

| Reasoned action approach (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010) |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

| Social identity approach (H Tajfel & Turner, 1986) |

+ |

++ |

++ |

|

| Status-power theory of relations (Theodore D. Kemper, 2017) |

– |

– |

+++ |

+ |

| BayesACT (Schroeder et al., 2016) |

+ |

+ |

++ |

|

Sources: theory, data, and experience

Models are integration devices, built from a variety of sources. Theory, data, and real-world experience all contribute to the usefulness of models that include artificial sociality (figure 1). The figure positions computational social simulation as a meeting place of these three elements. Different mixtures are possible, depending on the aim of modelling (Edmonds et al., 2019). Models range from purely theory-based ones that can illustrate core concepts, to models developed in participation with stakeholders that reflect real life, to highly complicated, data-fed models that can describe existing data or predict (generalize to) future measurements.

Artificial sociality as we propose it is, in the first instance, a theoretical concept. We believe that it has strong face validity in real life. This is by virtue of the empirical basis and broad scope of the theories involved. Integrating our concepts with data, for instance the never-ending stream of social media data, is a major challenge for the coming years.

Figure 1. Social simulation as a meeting place of theory, data and real life (Gert Jan Hofstede, 2018).

Model architectures

In artificial sociality we cannot get away with ideas only. Implementations are also needed, and functional computer code. In computer code, all the capabilities of our virtual world and of the agents that populate them, have to be unambiguously specified. This raises the issue of architecture. For instance, do agents have a body, a brain, and a soul? Do groups have common agency, or is that delegated to individuals? If the world is spatial, do we have instinctive reactions to moving objects? Is there “fast and slow” thinking as per many author’s writings (e.g. (Kahneman, 2011) (Zhu & Thagard, 2002) (Glöckner & Witteman, 2010)?

Currently, a thousand flowers are blooming in the computational modelling of human behaviour. This is a good way to search. We believe that one architecture will not cover all needs; in all likelihood many streams of research will dry up, and we’ll be left with a limited number of rather general-purpose architectures for different purposes. Many existing models and architectures deserve to be taken into account.

State of the art

Artificial sociality, by design, is integrative across its contributing disciplines. Scientists have tried to integrate research on human behaviour and society across disciplines as long as we know. This has, however, become progressively harder as disciplines have branched. Aristotle was still a polymath, but today this is hardly possible any more.

Some attempts that are meaningful for artificial sociality in our view merit mention here.

Conte and Gilbert and their legacy

In social simulation, the concept of sociality was introduced in the nineteen nineties. Psychological computer scientists Kathleen Carley and Allen Newell published their extensive essay “The Nature of the Social Agent” in 1994, in which they proposed that compared with “omniscient” economic agents, social agents have more limited processing capabilities, but a richer social environment. They will turn to socio-cultural clues instead of raw data (Carley & Newell, 1994). Cognitive psychologist Rosaria Conte and sociologist Nigel Gilbert are founders of the notion of “artificial societies” (Gilbert & Conte, 1995). They set out to define artificial sociality as a challenge for computational social simulation. Their reflections were crowded out of the public eye by the advent of the Web, and the increasing ubiquity of data as sources for modelling. Yet computational social modelling has remained focused on human social behaviour.

Flache et al. in a position paper explicitly dedicate their work to Conte, who died prematurely in 2016 (Flache et al., 2017). They plead for more research on the question that Robert Axelrod posed in 1997: “If people tend to become more alike in their beliefs, attitudes, and behavior when they interact, why do not all such differences eventually disappear?“(Robert Axelrod, 1997). Flache et al. discuss several models, the currency of which is opinions.

Jager also builds on a statement by Conte when he pleads for “EROS”, or more attention to social psychology in computational social simulation (Wander Jager, 2017). He reviews a number of theories that have been used in social simulation, none of which includes emotions. The most generic of these might be Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour (the most recent version of which the author calls Reasoned Action Approach (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010).

Other efforts

Work on active inference and a hierarchical (deep) Bayesian probabilistic view of the mind has led to more integrative models including of interpersonal inference (Moutoussis, Trujillo-Barreto, El-Deredy, Dolan, & Friston, 2014) and culture (Veissière, Constant, Ramstead, Friston, & Kirmayer, 2020). These models consider a long-standing view of human intelligence as being largely predictive rather than descriptive. That is, the mind is set up to seek information, and to interpret evidence, in ways that confirm prior beliefs.

A mid-range approach to sociality is taken by Shults and colleagues. They take domain-directed social scientific theory and develop agent-based models with agents embodying the theory. These tend to contain instantiated sociality elements such as fear. This includes terror management theory (Shults, Lane, et al., 2018) and intergroup dynamics under anxiety (Shults, Gore, et al., 2018).

Some computational modellers have built models of human behaviour suiting their purpose. This includes empathic agents, care robots, and the military. These models include some sociality, without necessarily using that term. Space forbids to deal with them at length. Interesting pointers are (Balke & Gilbert, 2014; Schlüter et al., 2017).

Consumat architecture

An example of an architecture that is appealing because of its simplicity, while including both content and a bit of sociality, is the Consumat (Wander Jager & Janssen, 2012; Wander Jager, Janssen, & Vlek, 1999). Consumats live in one group or network, not necessarily but possibly in a spatial world, in which they have repeated decisions to take about which they are more or less certain. In addition, they are more or less “happy” based on the outcome of their previous decisions. “Happiness” and “uncertainty” combined determine what they will do: repeat, imitate someone else, deliberate on content issues, or do a more elaborate social comparison. The currency of “happiness” is not further specified, making the Consumat model quite flexible. Embedding fundamental concepts of sociality (e.g., allusions to reference groups and uncertainty), Consumat takes the individual as a unit of concern, rendering it a flexible starting point for richer developments of artificial sociality that have a stronger emphasis on the structure the agent is embedded in. It has found quite a few applications. A more elaborate follow-up effort on Consumat called Humat is now being developed into publications.

FAtiMA

An engineering approach to sociality with considerable fidelity is FAtiMA (Mascarenhas et al., 2021). This open-source toolkit for social agents and robots includes prestige / status dynamics and social emotions. Status dynamics are called “social importance” in FAtiMA (Mascarenhas, Prada, Paiva, & Hofstede, 2013).

GRASP

The GRASP meta-model for sociality (Gert Jan Hofstede, 2019) is an attempt at capturing the bare essentials of sociality: Groups, Rituals, Affiliation, Status, and Power. GRASP is deliberately content-free. Its relational currency is status and power. It is based on the works of Kemper mentioned here, and on Hofstede’s and Minkov’s work on national cultures. Culture modifies the rules of the status-power action choices (G. Hofstede et al., 2010; Gert Jan Hofstede & Liu, 2019). A showcase model using GRASP, GRASP world (Gert Jan Hofstede & Liu, 2019; Gert Jan Hofstede & Liu, 2020), pictures the longevity of social groups based on the ease with which agents can leave a group in which they are subjected to power or receive insufficient status. The resulting patterns resemble social dynamics in different cultural environments.

Contextual Action Framework (CAFCA)

The CAFCA meta-model (figure 2) allows to disentangle levels of sociality and context. It was created to add on to Homo economicus models, and allows to classify existing model ontologies. Sociality implies moving to the bottom right of the model. CAFCA shows how far we still have to travel. One could extend it: a relational perspective is not included so far, nor is a multi-group world.

Figure 2: CAFCA, the Contextual Action Framework (Elsenbroich & Verhagen, 2016).

We can conclude that in response to Conte’s and Gilbert’s challenge, explicit opinions have received a lot of attention in computational social simulation, but emotions and feelings have not. We believe that this still leaves some phenomena unexplained. Opinions need not always be taken at face value, but can be manifestations of social feelings and emotions, e.g. love for one’s group. Computational agents are still often “autistic”, whereas real people have sociality at their core (Dignum, Hofstede, & Prada, 2014). Sociality can give them “biases”, “perspectives”, or “relational rationality” (Gert Jan Hofstede, Jonker, Verwaart, & Yorke-Smith, 2019) that can be derived from various theories.

Bayesian Affect Control Theory (BayesACT)

BayesACT is a dual process model that unifies decision theoretic deliberative reasoning with intuitive reasoning based on shared cultural affective meanings in a single Bayesian sequential model (Hoey, Schröder, & Alhothali, 2016; Schröder et al., 2016). Agents constructed according to this unified model are motivated by a combination of affective alignment (intuitive) and decision theoretic reasoning (deliberative), trading the two off as a function of the uncertainty or unpredictability of the situation. The model also provides a theoretical bridge between decision-making research and sociological symbolic interactionism. Bayes ACT is a promising new type of dual process model that explicitly and optimally (in the Bayesian sense) trades off motivation, action, beliefs and utility, and integrates cultural knowledge and norms with individual (rational) decision making processes. Hoey, et al. (in publication: Jesse Hoey, Neil J. MacKinnon, and Tobias Schroeder. Denotative and Connotative Management of Uncertainty: A Computational Dual-Process Model. To appear in Judgement and Decision Making, 16 (2), March 2021.2021) have shown how a component of the model is sufficient to account for some aspects of classic cognitive biases about fairness and dissonance, and have outlined how this new theory relates to parallel constraint satisfaction models.

Proposal: a relational world

We now put forward our own proposal for an architecture, not because we believe this is the only way to go, but in order to give an example of where a more radical take on sociality can lead.

Theory base

Theory versus data

We assume that data provide no more than a partial perspective on the phenomenon they are captured from. Only in concert with a theoretical concept will they attain meaning. For instance, consider today’s vast quantities of data on social media usage. Our communication on social media does not reflect all of our relations. Linking data and Kemper’s theory, we presume that people will use social media to claim status (e.g. show pictures of successes and important rituals), to confer status (e.g. like and follow others), and to use power (e.g. insult high-status others). There are also many relational motives that will not show in social media. People will hide shameful actions (e.g. failing, being exposed); they will protect some of their behaviours from some of their reference groups (e.g. their parents or spouses). People may fear the power of their own government, and stay away from some social media. Often people will seek information and interpret evidence in a way that confirms group acceptance, rather than in a way that confirms facts (Mercier and Sperber, 2009). Which members of a society go on which social media, and just how they select which things to show and which not to, are dependent upon relational dynamics that the data cannot show without help from theory. A theory is needed about the “why” of behaviour.

Building blocks: Complicated vs complex

We are aware of the tension between complicatedness of model structure and complexity of model outcomes (Sun et al., 2016). According to these authors, complex behaviour can be represented either by a model with few simple primitives, or by a very elaborate model. Our intuition is that a bottom-up approach with strong theory base and simple ontology is most promising. An analogy can illustrate this (figure 3). A complicated model architecture tends to be difficult to adapt. The price to pay for a simple, adaptive architecture is abstraction. To build a valid, versatile model with few primitives, just a few types of building blocks could suffice; only, one needs a great many of them.

Figure 3: giraffe models in Lego. From left to right: 1) Model that is valid but made of a complicated piece; 2) simple model with just 5 different rectangular shapes; 3) more complicated model with 15 different shapes of varied form; 4) simple model with few shapes but many pieces.

From theory to model

Implementing a theory from social science in a computational model is by no means straightforward. Typically, theories leave many elements unspecified. Model designers have to fill the gaps. For instance, the Social Identity Approach (SIA) has been used in computational modelling. It models agents as enacting a particular social role or identity that is context (institutionally) dependent and emotionally meaningful. From reviewing such papers, we learned how difficult it is to model a “complete” social world. We failed to find a single model yet that models SIA to its richness, and can actually be replicated. To accommodate this, a toolbox approach is used by the network project SIAM (SIAM: Social Identity in Agent-based Models, https://www.siam-network.online/), offering a set of formalizations that can then be specified for specific purposes/aims. Still, this is challenging. We believe that interdisciplinary work yields substantial benefits here.

Which theory

In selecting theories to work with, a thousand flowers can blossom. In our case, for creating models with relational agents that have simple ontology but great range, we believe that Kemper’s work, and SIA mentioned before could provide the Lego blocks. Both place individuals (called “agents” in what follows) in a rich world consisting of many groups with salience mechanisms. SIA gives agents both an individual and social identities. Kemper has no self but only reference groups, that is, groups existing in the mind of an individual, not necessarily in the outside world. For Kemper, the organism with its needs and urges is one reference group. Crucially, Kemper additionally gives the agents status and power motives; we believe this to be crucial for social agents. In SIA, agents act upon motives too (such as the need for positive distinctness and self-esteem), while status is achieved through comparison with outgroups. Heise’s Affect Control Theory (ACT) is similar to Kemper here, and more articulate for describing verbal communication; but it works for single groups only. Efforts at broadening ACT to multiple, overlapping and interacting groups, are currently underway (Hoey & Schröder, 2015).

In what follows we mainly lean on our interpretation of Kemper, as the most generic and simplest of these theories.

What, how and why

The “what” of our relational world consists of individuals and groups. A person can belong to several groups, and not everyone necessarily has the same shared belief about who belongs to which group. Furthermore, there will be an environment with certain affordances; we will come to this later.

Basic rules for the “why” are:

- What individuals do, is determined by the groups to which they affiliate. Those groups will act as reference groups.

- People’s choices depend on what they believe their reference groups want them to do.

- These beliefs are about status and power; they can be about individuals, or about groups.

- Status beliefs are about the status worthiness of actions, people, and groups; and about appropriate ways of claiming and conferring status.

- Power beliefs are about the power of people and groups; and about appropriate ways of using power.

- For obtaining what they want, people can choose between status tactics and power tactics.

- Status tactics involve claiming and conferring status. As long as conferrals exceed claims, they tend to be pleasant, and create trust. If claims exceed conferrals, people will feel insulted, and power tactics will be used.

- Power tactics involve coercion and deceit, and tend to lead to resentment and repercussions, except where power is perceived as legitimate.

- In practice, power use is often couched as status conferral; misunderstandings can also occur.

A model with these primitives would qualify as a GRASP model. The fine print of all of these rules – what is considered appropriate for whom, and in what circumstances – depends upon culture (Gert Jan Hofstede, 2013). This implies that the actual status-power game is quite complex and varied, even though there are few primitives.

The “How” would depend on the context, because the primitives need to be bound to instantiations. Here, the four “elementary forms of sociality” of anthropologist Alan Page Fiske could be useful. This may require a bit of introduction. Fiske, having carried out field studies in various civilizations, came up with four “ elementary forms of sociality” (Fiske, 1992). These are: communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching and market pricing. Fiske aims with these elementary types to bring unity to the myriad of psychological theories. He says people use these four structures when they “transfer things”, and interestingly, they correspond with four sales in which “things” can be compared: nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio. He comes up with a wide range of issues and situations where the four forms obtain. These are not mutually exclusive: we might use communal sharing in one setting, authority ranking in another, and market pricing in yet another. The balance will depend on the issue or group and on culture.

If we assume that the thing to exchange is social importance or, in Kemper’s sense, status, then the following obtains:

- Under communal sharing, it is the group, not the individual, that is the unit of status accordance, claiming, and worthiness

- Under authority ranking, there is a clear hierarchy in social importance, and status accords, as well as power exertion, are asymmetric based on ascription. “Quod licet Iovi not licet bovi” (“What the god Jupiter may do, a cow may not”).

- Under equality matching, each individual or group is equally worthy, should claim and be accorded the same amount of status.

- Under market pricing, there is no need for a moral stance, since the market decides.

The likelihood of these four forms is obviously culture-related. In particular, two of Hofstede’s dimensions seem relevant (see figure 4). These forms could directly be used as model mechanisms, or their emergence in agents could be studied based on Hofstede “software of the mind”.

Figure 4: Likelihood of Fiske’s elementary forms (quadrants) across Hofstede’s dimensions of culture (axes). Market pricing is indifferent to power distance.

Readers are invited to consider current events in their lives, or in the political arena, through a relational lens. Once one distinguishes the silent voice of reference groups, and the dynamics of mutual status and power use, one can also see historical continuity within the relational lives of people, groups, companies, and nations.

Proposed architecture

Figure 4 shows what we propose are key ingredients of our relational architectures for artificial sociality. There is a correspondence between the concepts in the four columns, with the left column reflecting the micro level of individual operation on the level of the organism to operationalise emotions and related individual-centred concepts. To our mind – and put forth in this paper – the most universal Lego blocks of artificial sociality are relational. In figure 5 we use Tönnies’ term Gemeinschaft for this. Figure 5 shows Kemper’s concepts of status, power and reference groups; but alternatives with similar relational content could be chosen. This relational column is always required. Depending on the application, the concepts in one or more of the other columns are needed. If they are included, they have to be mapped onto them, making status, power and reference groups the basic operational concepts for driving the model’s dynamics. For instance, emphatic agents need to feel and communicate emotions. Social robots need proxemics, i.e. to know the emotional impact of closeness, motion and posture; models that explain phenomena such as tribalism require individual-level concepts in addition to relational conceptions. Speaking to scale, simulations that model social complexity at the societal level, and are concerned with effects of policies require Gesellschaft concepts such as norms and institutions.

Examples for such models include the reaction to imposed behavioural constraints as part of the Covid-19 countermeasures employed throughout nation states – with vastly varying responses based on social structure and influence (expressed in the relational column) and individual motivations of various kinds, including perceived challenges to liberty, economic well-being, etc. Whatever the variable configuration of sociality elements, we require a conceptual mapping to the physical world, such as the operationalisation in status and power in currencies relevant to the society of concern (e.g., status symbols).

Figure 5 is organised into columns. The leftmost column is organismic on an objective sense, but subjectively perceived. The middle two are intersubjective, continually construed by people in interactions, although things in the Gesellschaft column tend to be perceived by many as objective (Searle, 1995). The rightmost column is about the physical world, considered objective but often perceived from a subjective, or rather intersubjective, stance.

The impact of this position is that a direct mapping from the physical world to emotions, or from money to behaviour, will not yield versatile models. Data based models without a strong social model of sound theoretical basis using e.g. financial actions to predict future economic behaviour, or past voting to predict future voting, might accommodate specific application cases, but their range of application across cases and time will be limited. More importantly, such models lack the explanatory potential that conceptual models of sociality can offer.

Figure 5: building block concepts for artificial sociality.

Conclusion

This position paper argues for a biological, relational turn in artificial human sociality. Such a turn will lay a foundation that can reconcile case-specific or discipline-specific model ontologies.

Artificial sociality has the potential to greatly enhance all knowledge technologies that impinge on the social world, including e.g. social robotics and body-worn AI devices.

In this paper we mainly aim to increase the usefulness of computational models of socio- ecological, -economical and -technical systems by tackling their social aspects on a par with the other ones, in a foundational, thorough way.

Many theories, in a great many disciplines, could possibly be used in constructing ontologies for artificial sociality. We provide some pointers and examples. We also present ideas for a “relational world” that could inspire modellers.

There is a lot of work to do.

Appendix: contributions to sociality from various disciplines

The appendix is sorted, admittedly somewhat arbitrarily, according to whether a field of research focuses more on the “What”, the “Why” or the “How” of behaviour. Within those three, the order is alphabetic.

Mainly the “what”

Anthropology

Computational simulations have been made of historic civilizations. In these, simulated populations live in a simulated environment. This requires a mix of historical data and assumptions, in particular about resources and / or social drives. If the various hypotheses that are implemented in the models hold, then the simulations could throw light on historical contingencies, or even reproduce the actual history. A famous example is the “artificial Anasazi” model by Epstein that ”replays” the rise and fall of the Anasazi civilization (Epstein & Axtell, 1996). The agents in this model have no sociality, but are constrained by resources. A recent example is e.g. a model of island colonization based on the concept of gregariousness (Fajardo, Hofstede, Vries, Kramer, & Bernal, 2020).

Another contribution from Anthropology is to study typical patterns of human social organization. The work of Alan Page Fiske is interesting in this respect. Fiske’s, four “ elementary forms of sociality” were mentioned before, in the context of figure 4 (Fiske, 1992). To repeat: communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching and market pricing.

Institutional Economics

A fundamental feature of humans is our ability to coordinate – at scale, that is. Humans can coordinate on group, societal and global level, both towards shared interests (e.g., emergence of economic and personal liberties in the French revolution; international treaties such as the Whaling convention), but, at times, they also contradict those (e.g., climate change, e.g., (Shivakoti, Janssen, & Chhetri, 2019)). In an attempt to identify the cause of prosperity or demise of societies, New Institutional Economics (North, 1990) integrate the many strands of human behaviour – including the ones outlined above. Rooted in our biology and manifested in our psychology, as humans we possess “minds as social institutions” (Castelfranchi, 2014) that continuously exercise coordination activities. Institutions, here understood as the “integrated systems of rules that structure social interactions” (Hodgson, 2015), or simply “rules of the game” (North, 1990) are the catalysts. They include sophisticated constructs such as written contracts and courts, enabling cooperation at scale (Milgrom, North, & Weingast, 1990); (North, Wallis, & Weingast, 2009), but also informal arrangements for resource governance (Ostrom, 1990), pointing to opportunities to address social dilemmas, such as the Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin, 1968).

Neurobiology and endocrinology

A model of sociality is more valid to the extent that it fits the evidence about our bodies. This includes the brain of course, with e.g. its mirror neurons that are a vehicle for empathy, but also older physiological systems such as the sympathetic (fear and anger) and parasympathetic (well-being) nerve system and the digestive system (all kinds of impulses, e.g. mediated by our gut microbiome). The recent semantic pointer theory of emotions (Kajic, Schroeder, Stewart, & Thagard, 2019) capitalizes on the mathematical apparatus of Affect Control Theory discussed above to embed the sociality of affective experience into neurobiological mechanisms through a neurocomputational simulation model.

Tönnies’ Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

A fundamental sociological theme that structures the arena of social behaviour is the dialectic between different forms of social organisation that represent anchor points for an integrated artificial sociality, namely Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society), introduced by (Tönnies, 1963 [1887]), and subsequently popularised by Weber. This distinction was part of an extended debate in early sociology about the core concepts of societal structure, where Gemeinschaft captures the characterisation of social ties observable in a social setting as primarily based on personal relationships, enacted roles and associated values as present in prototypical peasant societies prevalent at the time. Any interaction in those societies was based on what Tönnies referred to as natural will (“Wesenwille”) exhibited by members. Gesellschaft, in contrast, reflects the depersonalised counterpart in which individuals act in indirect form based on assigned roles, formal rules, processes and values, stereotypical structures associated with urban societies. Fittingly, Tönnies characterised motivations for any such interaction driven by rational will (“Kürwille”) encoded in the role individuals exhibit.

Likened to Durkheim’s differentiation between mechanical vs. organic solidarity (Durkheim, 1984), the concepts are stereotypical for the themes and worldviews that structured debate at the time. Instead of drawing on the particularities of either variant of this duality[1], they bear essentials that still apply to group dynamics found in modern societies.

Where behaviour is structured and planned, leading agents to create rules, react to imposed policy or enforce such, the representation of socio-institutional dynamics are of concern. While building and relying on concepts such as status and roles identified in the Gemeinschaft conception, concepts such as rules and governance structures extend beyond neurobiological and psychological bases of group formation, but are the mechanisms that lead to depersonalised coordination structures characteristic for the Gesellschaft interpretation of society. Doing so, models of artificial sociality can resemble the characteristics of real-world societies, including “growing” the complexity arising from systemic interdependencies of actors, roles and resources, and reflect the non-linearity of behavioural outcomes we can observe at scale.

Mainly the “why”

Behavioural biology

Behavioural biology has studied social behaviour of all kinds of animal, including those that resemble us very much. Frans de Waal stands out for his extensive studies about dominance, politics, reconciliation and pro-sociality among primate (Waal, 2009). Chimpanzees and bonobos in particular can teach us a lot about the sociality of Homo sapiens. Like chimps, we have bands of males fighting one another and dominating females. Like bonobos, we have female solidarity, social sexuality, and male reluctance to use their physical superiority.

Evolutionary biology

Our stress on the deep historic continuity of life in an unbroken chain of reproduction under variation implies that we see evolutionary biology as the mother of the social sciences. Our perspective owes to the work of authors such as De Waal, who concluded his discussion of morality in all kinds of animals, particularly primates, as follows: “We seem to be reaching a point at which science can wrest morality from the hands of philosophers” (Waal, 1996).

Evolutionary psychologist Turner argued that emotions have become much more important in humans than in other species, because we do not limit our contacts to either one predictable set of others, or an anonymous mass (J. E. Turner, 2007). We needed to find a relational compass. Our expressive faces and gestures, and our open faces, developed for that purpose.

Clinical psychology

Clinical psychologist Abraham Maslow gave us the famous model of human needs, by observing his patients and seeing an overarching pattern (Maslow, 1970). This model is antithetical to Homo economicus. The problem with it is that it is hard to operationalise. A more proximate concept in human drives is emotions (Frijda, 1986). Emotions have been used quite a bit in computational social simulation, e.g. the cognitive synthesis of emotions in the OCC model (Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1998). This has been used as underpinning of empathic computational agents (Dias, Mascarenhas, & Paiva, 2016).

Leadership psychology

The psychology of leadership naturally touches upon sociality. For instance, Van Vugt et al assert “leadership has been a powerful force in the biological and cultural evolution of human sociality” (Van Vugt & von Rueden, 2020). Human groups faced with problems of coordination and collective action turn to leadership for achieving collective agency. Different contexts have led to different leadership styles. Leaders can base their role on dominance (coercion), or on prestige (voluntary deference), and people still turn to more dominant leaders in times of stress.

Cultural psychology

Cultural psychology adds a comparative perspective to leadership psychology, showing that leadership styles and follower styles are co-dependent and have historical continuity across generations (G. Hofstede et al., 2010). It is also a discipline in its own right, and it shows how all of social psychology is in fact culture-dependent (Smith, Bond, & Kagitcibasi, 2006).

Social Psychology: Social Identity approach

A set of theories useful for modelling group behaviour and intergroup relations are presented in the Social Identity approach (SIA). SIA refers to the combination of Social Identity Theory (H Tajfel, 1982; H Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and Self-Categorization Theory (Reicher, Spears, & Haslam, 2010; J. C. Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987).

SIA proposes that social identification is a fundamental basis for collective behaviour, as people derive a significant part of their concept of self from the social groups they belong to (H. Tajfel, 1978; J. C. Turner et al., 1987). When a person’s identity as a group member becomes salient in a particular context, this affects who is seen as being an ingroup member versus someone outside of the group. When a social identity is salient, group membership becomes an important factor for individual beliefs and behaviour – what is important for the group becomes important for the individual. Moreover, groups have their own social norms and expected behaviours. For instance, thinking as members of collectives changes helping behaviour, as we are more likely to provide help to ingroup members (Levine, Prosser, Evans, & Reicher, 2005).

We deem SIA particularly well suited to model sociality, as it spans from the why (motives) to the how (e.g., saliency of social identities that impact on behavior, dynamics between groups), and connects the micro level of individuals with the macro level of groups, groups in groups, all the way up to societies. SIA has been used in social simulation to address diverse research questions from Sociology, opinion dynamics, Environmental Sciences and more (for two qualitative reviews see (Kopecky, Bos, & Greenberg, 2010; Scholz, Eberhard, Ostrowski, & Wijermans, 2021 (in press)). However, up to now there is no standard formalization, and formalizations found vary widely.

Mainly the “how”

Computational biology

Simulations include work of emergent patterns occurring in swarms and fish schools, based on simple positioning rules that fish and birds use while moving. A seminal contribution in the field of behavioural biology was made by the DomWorld model that showed, among other things, how spatial configurations in primate groups could emerge from dominance interactions (Charlotte K. Hemelrijk, 2000; Charlotte K Hemelrijk, 2011). Here, the contribution of a behavioural theory involving dominance and fear was crucial. The swarm and Domworld models also are instances of agent-based models. i.e. computational simulation models in which individuals live in a spatial world. These models have heterogeneity and path dependence, just like real historical developments.

Computational sociology

Sociologists have been at the origin of artificial sociality – avant la lettre. In 1971, mathematical sociologists Sakoda and Schelling published models showing self-organization in societies resulting in unintended, but robust collective patterns. The history of these models was recently traced by (Hegselmann, 2017). Computational sociologists have followed in their tracks, helped by the advent of simulation software (Hegselmann & Flache, 1998) (Deffuant, Carletti, & Huet, 2013). Recent computational models of this kind include emotions and their spread (Schweitzer & Garcia, 2010).

Development psychology

Developmental psychologists show how, during infancy, childhood and puberty, people acquire a more varied concept of the social world. For instance, rough-and-tumble play peaks in boys at the onset of adolescence (G.J. Hofstede, Dignum, Prada, Student, & Vanhée, 2015); among Dutch adolescents a nested set of reference groups develops, and girls are more prosocial overall than boys in a dictator game (Groep, Zanolie, & Crone, 2019; Güroglu, Bos, & Crone, 2014).

Economics

Economics came up with the concept of the profit-maximizing Homo economicus, useful as a standard with which to compare actual human behaviour, in contexts where “profit” can be defined. Not all contexts are like that, which is why behavioural economist Richard Thaler predicted that “Homo economicus will become more emotional” (Thaler, 2000). Experiments in behavioural economics and game theory have now shown that people have relational motives that moderate their actions, and often lead to “non-rational” behaviour that may be heavily culturally biased (Henrich et al., 2005). This is an important finding, because if the pleasantly simple Homo economicus model does not hold in reality, then what is the alternative?

Human motivation: Heise’s Affect Control Theory

Sociologists have also studied universals of human social motivations, either in small groups (Heise, 2013) or more generically (Theodore D. Kemper, 2017).

Heise posited Affect Control Theory, a relational theory on how people in small groups maintain relations. According to Affect Control Theory, every concept has not only a denotative meaning but also an affective meaning, or connotation, that varies along three dimensions:[1] evaluation – goodness versus badness, potency – powerfulness versus powerlessness, and activity – liveliness versus torpidity. His work has recently been elaborated upon in social simulation (Heise, 2013) and combined with decision theoretic (rational) reasoning models (Hoey et al., 2018).

Human motivation: Kemper’s relational world

Kemper, who worked with Heise sometimes, developed a model of human drives that is similar but less operationalized, and wider in scope. It distinguishes two major dimensions, derived empirically, having to do with coerced versus voluntary compliance: power, and status. Kemper’s word “status” is thus not a measure of power, but in a sense the opposite: it is a measure of not needing power. It has been dubbed “social importance” which captures the meaning but is lengthy (Mascarenhas et al., 2013). Readers will recognize these dimensions as the leadership styles named dominance and prestige in the above, and the connotations of goodness and powerfulness in Heise’s theory. Kemper used these two concepts to underpin a generic theory of emotions, to be discussed further down. He extended his idea into a “status-power theory of relations” involving also group life (Theodore D Kemper, 2011). Recently, he wrote a concise version of his theories that is amenable to computational modelling (Theodore D. Kemper, 2017). In a nutshell, his theory posits that all people live in a status-power relational world. Status comes in many currencies. It implies love, respect, attention, applause, financial rewards, sexual favours, or a thousand other things large and small. People strive to attain these things by “claiming status”, through actions, nonverbal behaviours, clothes, appearance, hobbies, exploits, or vested in formal roles. This position paper, for instance, constitutes a status claim by its authors, in the currency of scientific credibility.

People thus strive for status. Yet they are not just selfish, but also motivated by love and affection to “confer status” upon others they deem worthy, or even upon heroes, symbols, deities, or groups. One person’s status worthiness is another one’s motive for conferring status. Status is thought to be a key driving factor in sustainable/durable inequality (Ridgeway, 2019).

When status claims fail, or when love is unrequited, people could respond by sadness, or by anger. In the latter case they might try to obtain the denied items by coercion, “power”. How to play the status-power game in life is something that people learn in their childhood, in a conjunction of “nature and nurture”. The fine print of the status-power game is cultural. For instance, some societies put a lot of value on power as a source of status, others do not; some societies divide status worthiness equally across people, others do not.

Two scientists who took their work and linked it to other disciplines could form an important source of inspiration for advances in sociality. They are Theodore Kemper and Antonio Damasio.

Socio-psycho-neurology: Kemper

Sociologist Theodore D. Kemper was mentioned above. He proposed a “Social interactional theory of emotions” that explicitly integrates socio-physiology of emotions, including work on the fit between neurophysiology and his own status-power model of relations (Theodore D Kemper, 1978). This is known in the literature as the “autonomic specificity hypothesis”, and Kemper’s theory supported it strongly, by linking neurotransmitters of the sympathetic nervous system with unpleasant events involving status loss (noradrenaline) and subjection to power (epinephrine). Acetylcholine, released by the parasympathetic nervous system, was associated with fulfilled status and power needs.

Kemper’s work was reviewed by sociologists with awe and admiration, but also with disbelief (Fine, 1981). It went largely forgotten. Recent work lends support to the specificity hypothesis once more, but without using Kemper’s theory, or integrating the findings across disciplines (McGinley & Friedman, 2017). Obviously, Kemper was ahead of his time. We believe his work is still innovative and important for the way in which it links neurobiology and sociology. According to Kemper, emotions tell their bearer whether survival is being facilitated (well-being signifies adequate status and power) or threatened (depression and fear signify reduced status or threat of others’ power) by events. Emotions are felt by individuals, carried by hormones, but induced by social situations involving relations between people. This is not to say that artificial sociality should include neurobiology. The importance of Kemper’s work is that it links disciplines operating at different levels of analysis, and shows the neurological roots of status and power motives.

Neuroscience: Damasio

Neuroscientist Damasio (2018) covers similar ground as Kemper does, but approaching from the opposite direction. Having noticed in his career that people are driven by more than their brains, he investigates the role of “feelings” in human cultural activity. Feelings, for Damasio, include avoidance of pain and suffering, and the pursuit of well-being and pleasure. They are more bodily, and less articulate, than emotions. For instance, “ache” is a feeling, “shame” is an emotion; feelings and emotions often co-occur. Damasio finds that feelings are not a new invention of evolutionary history, but are manifest in any single-cellular organism. He argues that any organism must maintain homeostasis of its inner environment in order to stay alive. “Feelings are the mental expressions of homeostasis” (ibid., p.6). Since all of our ancestors in the billion-years evolutionary history have had to maintain homeostasis in order to reproduce, “homeostasis, acting under the cover of feeling, is the functional thread that links early life-forms to the extraordinary partnership of bodies and nervous systems [of ourselves]”. Feelings are a primitive, powerful mechanism: we feel with our skins and our guts. Brains are just the latest addition to the organismic arsenal for maintaining homeostasis.

Damasio then turns to the social world: “In their need to cope with the human heart in conflict, in their desire to reconcile the contradictions posed by suffering, fear, anger, and the pursuit of well-being, humans turned to wonder and awe and discovered music making, painting, dancing and literature. They continued their efforts by creating the often beautiful and sometimes frayed epics that go by such names as religious belief, philosophical enquiry, and political governance.” (ibid., p. 8).

The impact of Damasio’s work is to downplay the role of intellect and mind in the shaping of collective behaviours, in favour of feelings. Damasio legitimizes gut feelings as motivators. It does not take much imagination to summarize his picture of feelings as a status-power world in the sense found by Kemper. Having adequate status causes well-being; being confronted with power causes fear. Since the world of feelings and emotions is less complex than the world of ideas, primacy of the former reduces the number of primitives required to model sociality, compared with a “brainy” world.

Damasio and Kemper together lay a strong foundation of consilience to the work of artificial sociality. Both give a central role to the organism, but not to the “self”. Kemper considers the “self” a superfluous notion; he considers the organism, with its feelings, as only one of the many reference groups that influence a person’s actions. Damasio shows that our organism has a life of its own, only some of which reaches our consciousness.

Acknowledgements

We thank the 150 attendants to the Artificial Sociality track at SocSimFest 2021, many of whom made valuable remarks that helped us.

[1] Durkheim puts a stronger emphasis on the stereotypical micro-level mechanisms in both forms of solidarity, such as enforcement mechanisms.

References

Axelrod, R. (1997). Advancing the Art of Simulation in the Social Sciences. 21-40.

Axelrod, R. (1997). The Dissemination of Culture; A model with local convergence and global polarization. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(2), 203-226. doi:10.1177/0022002797041002001

Balke, T., & Gilbert, N. (2014). How Do Agents Make Decisions? A Survey. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 17(4:13). doi:10.18564/jasss.2687

Beugelsdijk, S., & Welzel, C. (2018). Dimensions and Dynamics of National culture: Synthesizing Hofstede with Inglehart. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(10), 1469-1505. doi:10.1177/0022022118798505

Carley, K., & Newell, A. (1994). The nature of the social agent. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 19(4), 221-262.

Castelfranchi, C. (2014). Minds as social institutions. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. doi:10.1007/s11097-013-9324-0

Damasio, A. R. (2018). The Strange Order of things: Life, Feeeling, and the Making of Cultures: Pantheon.

Deffuant, G., Carletti, T., & Huet, S. (2013). The Leviathan Model: Absolute Dominance, Generalised Distrust, Small Worlds and Other Patterns Emerging from Combining Vanity with Opinion Propagation. JASSS, 16(1), 5. http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/16/1/5.html

Diallo, S. Y., Shults, F. L. R., & Wildman, W. J. (2020). Minding morality: ethical artificial societies for public policy modeling. AI and Society. doi:10.1007/s00146-020-01028-5

Diamond, J. (1999). Guns, Germs and Steel: The fates of human societies: Norton & co.

Dias, J., Mascarenhas, S., & Paiva, A. (2016). FAtiMA Modular: Towards an Agent Architecture with a Generic Appraisal Framework. In Emotion Modeling (Vol. LNCS 8750, pp. 44-56): Springer.

Dignum, F., Hofstede, G. J., & Prada, R. (2014, 2014). From autistic to social agents. Paper presented at the 13th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, AAMAS 2014.

Durkheim, E. (1984). The Division of Labour in Society.

Edmonds, B., Le Page, C., Bithell, M., Chattoe-Brown, E., Grimm, V., Meyer, R., . . . Squazzoni, F. (2019). Different Modelling Purposes. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 22(3), 6. doi:10.18564/jasss.3993

Edmonds, B., & Moss, S. (2005). From KISS to KIDS — An `Anti-simplistic’ Modelling Approach. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3415, 130-144. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-32243-6_11

Eliot, L. (2009). brain, blue brain: How small differences grow into troublesome gaps – and what we can do about it. Boston: Mariner Books.

Elsenbroich, C., & Verhagen, H. (2016). The simplicity of complex agents: a Contextual Action Framework for Computational Agents. Mind & Society, 15(1), 131-143.

Epstein, J. M. (2006). Generative Social Science: Studies in Agent-Based Computational Modeling: Princeton University Press.

Epstein, J. M., & Axtell, R. (1996). Growing artificial societies: social science from the bottom up. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Fajardo, S., Hofstede, G. J., Vries, M. d., Kramer, M. R., & Bernal, A. (2020). Gregarious Behavior, Human Colonization and Social Differentiation: An Agent-based Model. JASSS, 23(4), 11. http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/23/4/11.html

Fine, G. A. (1981). Book review: A Social Interactional Theory of Emotions. Social Forces, 59(4), 1332-1333.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and Changing Behavior: the Reasoned Action Approach: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis.