By Sven Banisch

Department for Sociology, Institute of Technology Futures

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology

It has become common in the opinion dynamics community to categorize different models according to how two agents i and j change their opinions oi and oj in interaction (Flache et al. 2017, Lorenz et al. 2021, Keijzer and Mäs 2022). Three major classes have emerged. First, models of assimilation or positive social influence are characterized by a reduction of opinion differences in interaction as achieved, for instance, by classical models with averaging (French 1956, Friedkin and Johnson 2011). Second, in models with repulsion or negative influence agents may be driven further apart if they are already too distant (Jager and Amblard 2005, Flache and Macy 2011). Third, reinforcement models are characterized by the fact that agents on the same side of the opinion spectrum reinforce their opinion and go more extreme (Martins 2008, Banisch and Olbrich 2019, Baumann et al. 2020). While this categorization is useful for differentiating different classes of models along with their assumptions, for assessing if different model implementations belong to the same class, and for understanding the macroscopic phenomena that can be expected, it is not without problems and may lead to misclassification and misunderstanding.

This comment aims to provide a critical — yet constructive — perspective on this emergent theoretical language for model synthesis and comparison. It directly links to a recent comment in this forum (Carpentras 2023) that describes some of the difficulties that researchers face when developing empirically grounded or validated models of opinion dynamics which often “do not conform to the standard framework of ABM papers”. I have made very similar experiences during a long review process for a paper (Banisch and Shamon 2021) that, to my point of view, rigorously advances argument communication theory — and its models — through experimental research. In large part, the process has been so difficult because authors from different branches of opinion dynamics speak different languages and I feel that some conventions may settle us into a “vicious cycle of isolation” (Carpentras 2020) and closure. But rather than suggesting a divide into theoretically and empirically oriented opinion dynamics research, I would like to work towards a common ground for empirical and theoretical ABM research by a more accurate use of opinion dynamics language.

The classification scheme for basic opinion change mechanisms might be particularly problematic for opinion models that take cognitive mechanisms and more complex opinion structures into account. These often more complex models are required in order to capture linguistic associations observed in real debates, or to better link to a specific experimental design. In this note, I will look at argument communication models (ACMs) (Mäs and Flache 2013, Feliciani et al. 2020, Banisch and Olbrich 2021, Banisch and Shamon 2021) to show how theoretically-inspired model classification can be misleading. I will first show that the classical ACM by Mäs and Flache (2013) has been repeatedly misclassified as a reinforcement model while it is purely averaging when looking at the implied attitude changes. Second, only when biased processing is incorporated into argument-induced opinion changes such that agents favor arguments aligned with their opinion, ACMs become reinforcing or contagious (Lorenz et al. 2021). Third, when biases become large, ACMs may feature patterns of opinion adaptation which — according to the above categorization — are considered as negative influence.

Opinion change functions for the three model classes

Let us start by looking at the opinion change assumptions entailed in “typical” positive and negative influence and reinforcement models. Following Flache et al. (2017) and Lorenz et al. (2021), we will consider opinion change functions of the following form:

Δoi=f(oi,oj).

That is, the opinion change of agent i is given as a function of i’s opinion and the opinion of an interaction partner j. This is sufficient to characterize an ABM with dyadic interaction where repeatedly two agents with two opinions (oi,oj) are chosen at random and f(oi,oj) is applied. Here we deal with continuous opinions in the interval oi∈[-1,1] in the context of which the model categorizations have been mainly introduced. Notice that some authors refer to f as an influence response function, but as this notion has been introduced in the context of discrete choice models (Lopez-Pintado and Watts 2008, Mäs 2021) governing the behavioral response of agents to the behavior in their neighborhood, we will stick to the term opinion change function (OCF) here. OCFs hence map from two opinions to the induced opinion change: [-1,1]2→R and we can depict them in form of a contour density vector plot as shown in Figure 1.

The most simple form of a positive influence OCF is weighted averaging:

Δoi=μ(oj-oi).

That is, an agent i approaches the opinion of another agent j by a parameter μ times the distance between i and j. This function is shown on the left of Figure 1. If oj<oi (above the diagonal where oj=oi) approaches the opinion of from below. The opinion change is positive indicating a shift to the right (red shades). If oi<oj (below the diagonal) i approaches j from above implying negative opinion change and shift to the left (blue shades). Hence, agents left to the diagonal will shift rightwards, and agents right to the diagonal will shift to the left.

Macroscopically, these models are well-known to converge to consensus on connected networks. However, Deffuant et al. (2000) and Hegselmann and Krause (2002) introduced bounded confidence to circumvent global convergence — and many others have followed with more sophisticated notions of homophily. This class of models (models with similarity bias in Flache et al. 2017) affects the OCF essentially by setting f=0 for opinion pairs that are beyond a certain distance threshold from the diagonal. I will briefly comment on homophily later.

Negative influence can be seen as an extension of bounded confidence such that opinion pairs that are too distant will lead to a repulsive force driving opinions further apart. As the review by Flache et al. (2017), we rely on the OCF from Jager and Amblard (2005) as the paradigmatic case. However, the function shown in Flache et al. (2017) seems to be slightly mistaken so we resort to the original implementation of negative influence by Jager and Amblard (2005):

That is, if the opinion distance |oi–oj| is below a threshold u, we have positive influence as before. If the distance |oi–oj| is larger than a second threshold t, there is repulsive influence such that i is driven away from j. In between these two thresholds, there is a band of no opinion change f(oi,oj)=0 just as for bounded confidence. This function is shown in the middle of Figure 1 (u=0.4 and t=0.7). In this case, we observe a left shift towards a more negative opinion (blue shades) above the diagonal and sufficiently far from it (governed by t). By symmetry, a right shift to a more positive opinion is observed below the diagonal when oi is sufficiently larger than oj. Negative influence is at work in these regions such that an agent i at the right side of the opinion scale (oi<0) will shift towards an even more rightist position when interacting with a leftist agent with opinion oj>0 (same on the other side).

Notice also that this implementation does not ensure opinions are bound to the interval [-1,1] as negative opinion changes are present even if oi is already at a value of -1. Vice versa for the positive extreme. Typically this is artificially resolved by forcing opinions back to the interval once they exceed it, but a more elegant and psychologically motivated solution has been proposed in Lorenz et al. (2021) by introducing a polarity factor (incorporated below).

Finally, reinforcement models are characterized by the fact that agents on the same side of the opinion scale become stronger in interaction. As pointed out by Lorenz et al. (2021) the most paradigmatic case of reinforcement is simple contagion and the OCF used here for illustration is adopted from their notion:

Δoi=αSign(oj).

That is, agent j signals whether she is in favor (oj>0) or against (oj<0) the object of opinion, and agent i adjusts his opinion by taking a step α in that direction. This means that positive opinion change is observed whenever i meets an agent with an opinion larger than zero. Agent i’s opinion will shift rightwards and become more positive. Likewise, a negative opinion change and shift to the left is observed whenever oj is negative. Notice that, in reinforcement models, opinions assimilate when two agents of opposing opinions interact so that induced opinion changes are similar to positive influence in some regions of the space. As for negative influence, this OCF does not ensure that opinions remain in [-1,1], but see Banisch and Olbrich (2019) for a closely related reinforcement learning model that endogenously remains bound to the interval.

Argument-induced opinion change

Compared to models that fully operate on the level of opinions oi∈[-1,1] and are hence completely specified by an OCF, argument-based models are slightly more complex and the derivation of OCFs from the model rules is not straightforward. But let us first, at least briefly, describe the model as introduced in Banisch and Shamon (2021).

In the model, agents hold a number of M pro- and M counterarguments which may be either zero (disbelief) or one (belief). The opinion of an agent is defined as the number of pro versus con arguments. For instance, if an agent believes 3 pro arguments and only one con argument her opinion will be oi=2. For the purposes of this illustration, we will normalize opinions to lie in between -1 and 1 which is achieved by division through M: oi→oi/M. In interaction, agent j acts as a sender articulating an argument to a receiving agent i. The receiver takes over that argument with probability

where the function dir(arg) designates whether the new argument implies positive or negative opinion change. This probability accounts for the fact that agents are more willing to accept information that coheres with their opinion. The free parameter β models the strength of this bias.

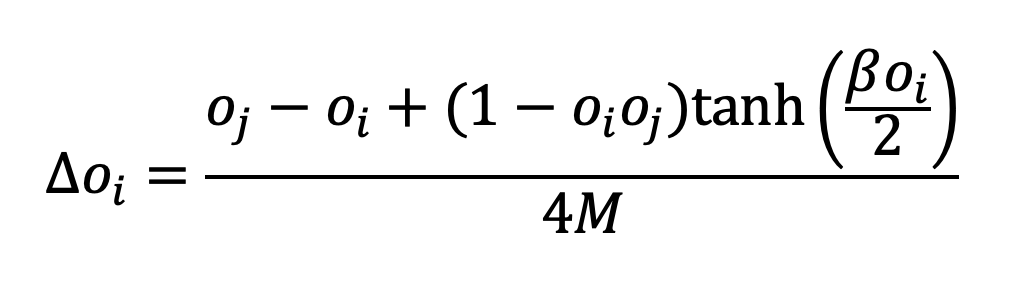

From these rules, we can derive an OCF of the form Δoi=f(oi,oj) by considering (i) the probability that chooses an argument with a certain direction and (ii) the probability that this argument is new to (see Banisch and Shamon 2021 on the general approach):

Notice that this is an approximation because the ACM is not reducible to the level of opinions. First, there are several combinations of pro and con arguments that give rise to the same opinion (e.g. an opinion of +1 is implied by 4 pro and 3 con arguments as well as by 1 pro and 0 con arguments). Second, the probability that ’s argument is new to depends on the specific argument strings, and there is a tendency that these strings become correlated over time. These correlations lead to memory effects that become visible in the long convergence times of ACMs (Mäs and Flache 2013, Banisch and Olbrich 2021, Banisch and Shamon 2021). The complete mathematical characterization of these effects is far from trivial and beyond the scope of this comment. However, they do not affect the qualitative picture presented here.

- Argument models without bias are averaging.

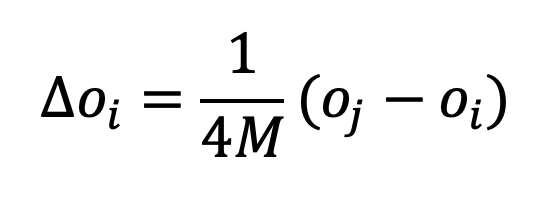

With that OCF it becomes directly visible that it is incorrect to place the original ACM (without bias) within the class of reinforcement models. No bias means β=0, in which case we obtain:

That is, we obtain the typical positive influence OCF with μ=1/4M shown on the left of Figure 2.

This may appear counter-intuitive (it did in the reviews) because the ACM by Mäs and Flache (2013) generates the idealtypic pattern of bi-polarization in which two opinion camps approach the extreme ends of the opinion scale. But this macro effect is an effect of homophily and the associated changes in the social interaction structure. It is important to note that homophily does not transform an averaging OCF into a reinforcing one. When implemented as bounded confidence it only cuts off certain regions by setting f(oi,oj)=0. Homophily is a social mechanism that acts at another layer and its reinforcing effect in ACMs is conditional on the social configuration of the entire population. In the models, it generates biased argument pools in a way strongly reminiscent of Sunstein’s law of group polarization (2002). That given, the main result by Mäs and Flache (2013) („differentiation without distancing“) is all the more remarkable! But it is at least misleading to associate it with models that implement reinforcement mechanisms (Martins 2008, Banisch and Olbrich 2019, Baumann et al. 2020).

2. Argument models with moderate bias are reinforcing.

It is only when biased processing is enabled that ACMs become what is called reinforcement models. This is clearly visible on the right of Figure 2 where a bias of β=2 has been used. If, in Figure 1, we accounted for the polarity effect, circumventing that opinions exceed the opinion interval (Lorenz et al. 2021), the match between the right-hand sides of Figures 1 and 2 would be even more remarkable.

This transition from averaging to reinforcement by biased processing shows that the characterization of models in terms of induced opinion changes (OCF) may be very useful and enables model comparison. Namely, at the macro scale, ACMs with moderate bias behave precisely as other reinforcement models. In a dense group, it will lead to what is called group polarization in psychology: the whole group collectively shifts to an extreme opinion at one side of the spectrum. On networks with communities, these radicalization processes may take different directions in different parts of the network and feature collective-level bi-polarization (Banisch and Olbrich 2019).

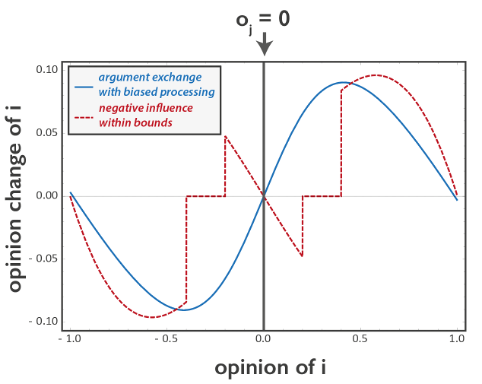

- Argument models with strong bias may appear as negative influence.

Finally, when the β parameter becomes larger, the ACM leaves the regime of reinforcement models and features patterns that we would associate with negative influence. This is shown in the middle of Figure 2. Under strong biased processing, a leftist agent i with an opinion of (say) oi=-0.75 will shift further to the left when encountering a rightist agent j with an opinion of (say) oj=+0.5. Within the existing classes of models, such a pattern is only possible under negative influence. ACMs with biased processing offer a psychologically compelling alternative, and it is an important empirical question whether observed negative influence effects (Bail et al. 2018) are actually due to repulsive forces or due to cognitive biases in information reception.

The reader will notice that, when looking at the entire OCF in the space spanned by (oi,oj)∈[-1,1]2, there are qualitative differences between the ACM and the OCF defined in Jager and Amblard (2005). The two mechanisms are different and imply different response functions (OCFs). But for some specific opinion pairs the two functions are hardly discernible as shown in the next figure. The blue solid curve shows the OCF of the argument model for β=5 and an agent i interacting with a neutral agent j, i.e. f(oi,0). The ACM with biased processing is aligned with experimental design and entails a ceiling effect so that maximally positive (negative) agents cannot further increase (decrease) their opinion. To enable fair comparison, we introduce the polarity effect used in Lorenz et al. (2021) to the negative influence OCF ensuring that opinions remain within [-1,1]. That is, for the dashed red curve the factor (1- oi2) (cf. Eq. 6 in Lorenz et al. 2021) is multiplied with the function from Jager and Amblard (2005) using u=0.2 and t=0.4. In this specific case, the shapes of the two OCFs are extremely similar. Experimental test would hardly distinguish the two.

Macroscopically, strong biased processing leads to collective bi-polarization even in the absence of homophily (Banisch and Shamon 2021). This insight has been particularly puzzling and mind-boggling to some of the referees. But the reason for this to happen is precisely the fact that ACMs with biased processing may lead to negative influence opinion change phenomena. This indicates, among other things, that one should be very careful to draw collective-level conclusions such as a depolarizing effect of filter bubbles from empirical signatures of negative influence (Bail et al. 2018). While their argumentation seems at least puzzling on the ground of “classical” negative influence models (Mäs and Bischofberger 2015, Keijzer and Mäs 2022), it could be clearly rejected if the empirical negative influence effects are attributed to the cognitive mechanism of biased processing. In ACMs, homophily generally enhances polarization tendencies (Banisch and Shamon 2021).

What to take from here?

Opinion dynamics is at a challenging stage! We have problems with empirical validation (Sobkowicz 2009, Flache et al. 2017) but seem to not sufficiently acknowledge those who advance the field into that direction (Chattoe-Brown 2022, Keijzer 2022, Carpentras 2023). It is greatly thanks to the RofASSS forum that these deficits have become visible. Against that background, this comment is written as a critical one, because developing models with a tight connection to empirical data does not always fit with the core model classes derived from research with a theoretical focus.

The prolonged review process for Banisch and Shamon (2021) — strongly reminiscent of the patterns described by Carpentras (2023) — revealed that there is a certain preference in the community to draw on models building on “opinions” as the smallest and atomic analytical unit. This is very problematic for opinion models that take cognitive mechanisms and complexity into due account. Moreover, we barely see “opinions” in empirical measurements, but rather observe argumentative statements and associations articulated on the web and elsewhere. To my point of view, we have to acknowledge that opinion dynamics is a field that cannot isolate itself from psychology and cognitive science because intra-individual mechanisms of opinion change are at the core of all our models. And just as new phenomena may emerge as we go from individuals to groups or populations, surprises may happen when a cognitive layer of beliefs, arguments, and their associations is underneath. We can treat these emergent effects as mere artifacts of expendable cognitive detail, or we can truly embrace the richness of opinion dynamics as a field spanning multiple levels from cognition to macro social phenomena.

On the other hand, the analysis of the OCF “emerging” from argument exchange also points back to the atomic layer of opinions as a useful reference for model comparisons and synthesis. Specific patterns of opinion updates emerge in any opinion dynamics model however complicated its rules and their implementation might be. For understanding macro effects, more complicated psychological mechanisms may be truly relevant only in so far as they imply qualitatively different OCFs. The functional form of OCFs may serve as an anchor of reference for “model translations” allowing us to better understand the role of cognitive complexity in opinion dynamics models.

What this research comment — clearly overstating at the very front — also aims to show is that modeling based in psychology and cognitive science does not automatically mean we leave behind the principles of parsimony. The ACM with biased processing has only a single effective parameter (β) but is rich enough to span over three very different classes of models. It is averaging if β=0, it behaves like a reinforcement model with moderate bias (β=2), and may look like negative influence for larger values of . For me, this provides part of an explanation for the misunderstandings that we experienced in the review process for Banisch and Shamon (2021). It’s just inappropriate to talk about ACMs with biased processing within the categories of “classical” models of assimilation, repulsion, and reinforcement. So the review process has been insightful, and I am very grateful that traditional Journals afford such productive spaces of scientific discourse. My main “take-home” from this whole enterprise is that current language enjoins caution to not mix opinion change phenomena with opinion change mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Sociology and Computational Social Science group at KIT — Michael Mäs, Fabio Sartori, and Andreas Reitenbach — for their feedback on a preliminary version of this commentary. I also thank Dino Carpentras for his preliminary reading.

This comment would not have been written without the three anonymous referees at Sociological Methods and Research.

References

Flache, A., Mäs, M., Feliciani, T., Chattoe-Brown, E., Deffuant, G., Huet, S., & Lorenz, J. (2017). Models of social influence: Towards the next frontiers. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 20(4),2 http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/20/4/2.html. DOI:10.18564/jasss.3521

Lorenz, J., Neumann, M., & Schröder, T. (2021). Individual attitude change and societal dynamics: Computational experiments with psychological theories. Psychological Review, 128(4), 623. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/rev0000291

Keijzer, M. A., & Mäs, M. (2022). The complex link between filter bubbles and opinion polarization. Data Science, 5(2), 139-166. DOI:10.3233/DS-220054

French Jr, J. R. (1956). A formal theory of social power. Psychological review, 63(3), 181. DOI:10.1037/h0046123

Friedkin, N. E., & Johnsen, E. C. (2011). Social influence network theory: A sociological examination of small group dynamics (Vol. 33). Cambridge University Press.

Jager, W., & Amblard, F. (2005). Uniformity, bipolarization and pluriformity captured as generic stylized behavior with an agent-based simulation model of attitude change. Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory, 10, 295-303. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10588-005-6282-2

Flache, A., & Macy, M. W. (2011). Small Worlds and Cultural Polarization. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 35, 146-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.2010.532261

Martins, A. C. (2008). Continuous opinions and discrete actions in opinion dynamics problems. International Journal of Modern Physics C, 19(04), 617-624. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129183108012339

Banisch, S., & Olbrich, E. (2019). Opinion polarization by learning from social feedback. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 43(2), 76-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.2018.1517761

Baumann, F., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Sokolov, I. M., & Starnini, M. (2020). Modeling echo chambers and polarization dynamics in social networks. Physical Review Letters, 124(4), 048301. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.048301

Carpentras, D. (2023). Why we are failing at connecting opinion dynamics to the empirical world. 8th March 2023. https://rofasss.org/2023/03/08/od-emprics/

Banisch, S., & Shamon, H. (2021). Biased Processing and Opinion Polarisation: Experimental Refinement of Argument Communication Theory in the Context of the Energy Debate. Available at SSRN 3895117. The most recent version is available as an arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10117.

Carpentras, D. (2020) Challenges and opportunities in expanding ABM to other fields: the example of psychology. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 20th December 2021. https://rofasss.org/2021/12/20/challenges/

Mäs, M., & Flache, A. (2013). Differentiation without distancing. Explaining bi-polarization of opinions without negative influence. PloS One, 8(11), e74516. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074516

Feliciani, T., Flache, A., & Mäs, M. (2021). Persuasion without polarization? Modelling persuasive argument communication in teams with strong faultlines. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 27, 61-92. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10588-020-09315-8

Banisch, S., & Olbrich, E. (2021). An Argument Communication Model of Polarization and Ideological Alignment. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(1). https://www.jasss.org/24/1/1.html

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.4434

Lorenz, J., Neumann, M., & Schröder, T. (2021). Individual attitude change and societal dynamics: Computational experiments with psychological theories. Psychological Review, 128(4), 623. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/rev0000291

Mäs, M. (2021). Interactions. In Research Handbook on Analytical Sociology (pp. 204-219). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lopez-Pintado, D., & Watts, D. J. (2008). Social influence, binary decisions and collective dynamics. Rationality and Society, 20(4), 399-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463108096787

Deffuant, G., Neau, D., Amblard, F., & Weisbuch, G. (2000). Mixing beliefs among interacting agents. Advances in Complex Systems, 3(01n04), 87-98.

Hegselmann, R., & Krause, U. (2002). Opinion Dynamics and Bounded Confidence Models, Analysis and Simulation. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 5(3),2. https://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/5/3/2.html

Sunstein, C. R. (2002). The Law of Group Polarization. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 10(2), 175-195. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.199668

Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M. F., … & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), 9216-9221. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804840115

Mäs, M., & Bischofberger, L. (2015). Will the personalization of online social networks foster opinion polarization? Available at SSRN 2553436. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2553436

Sobkowicz, P. (2009). Modelling opinion formation with physics tools: Call for closer link with reality. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 12(1), 11. https://www.jasss.org/12/1/11.html

Chattoe-Brown, E. (2022). If You Want To Be Cited, Don’t Validate Your Agent-Based Model: A Tentative Hypothesis Badly In Need of Refutation. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 1 Feb 2022. https://rofasss.org/2022/02/01/citing-od-models/

Keijzer, M. (2022). If you want to be cited, calibrate your agent-based model: a reply to Chattoe-Brown. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. 9th Mar 2022. https://rofasss.org/2022/03/09/Keijzer-reply-to-Chattoe-Brown

Banisch, S. (2023) “One mechanism to rule them all!” A critical comment on an emerging categorization in opinion dynamics. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 26 Apr 2023. https://rofasss.org/2023/04/26/onemechanism

© The authors under the Creative Commons’ Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND) Licence (v4.0)