By Bruce Edmonds1, Dino Carpentras2, Nick Roxburgh3, Edmund Chattoe-Brown4 and Gary Polhill3

- Centre for Policy Modelling, Manchester Metropolitan University

- Computational Social Science, ETH Zurich

- James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen

- University of Leicester

“Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in shape of a camel?

Polonius: By the mass, and ‘tis like a camel, indeed.

Hamlet: Methinks it is like a weasel.

Polonius: It is backed like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale?

Polonius: Very like a whale.”

Models and Generality

The essence of a model is that it represents – if it is not a model of something it is not a model at all (Zeigler 1976, Wartofsky 1979). A random bit of code or set of equations is not a model. The point of a model is that one can use the model to infer or understand some aspects about what it represents. However, models can represent a variety of kinds of things in a variety of ways (Edmonds & al. 2019) – it can represent ideas, correspond to data, or aspects of other models and it can represent each of these in either a vague or precise manner. To completely understand a model – its construction, properties and working – one needs to understand how it does this mapping. This piece focuses attention on this mapping, rather than the internal construction of models.

What a model reliably represents may be a single observed situation, but it might satisfactorily represent more than one such situation. The range of situations that the model satisfactorily represents is called the “scope” of the model (what is “satisfactory” depending on the purpose for which the model is being used). The more extensive the scope, the more “general” we say the model is. A model that only represents one case has no generality at all and may be more in the nature of a description.

There is a hunger for general accounts of social phenomena (let us call these ‘theories’). However, this hunger is often frustrated by the sheer complexity and ‘messiness’ involved in such phenomena. If every situation we observe is essentially different, then no such theory is possible. However, we hope that this is not the case for the social world and, indeed, informal observation suggests that there is, at least some, commonality between situations – in other words, that some kind of reliable generalisation about social phenomena might be achievable, however modest (Merton 1968). This piece looks at two kinds of applicability – analogical applicability and empirical applicability – and critiques those that conflate them. Although the expertise of the authors is in the agent-based modelling of social phenomena, and so we restrict our discussion to this, we strongly suspect that our arguments are true for many kinds of modelling across a range of domains.

In the next sections we contrast two uses for models: as analogies (ways of thinking about observed systems) and those that intend to represent empirical data in a more precise way. There are, of course, other uses of model such as that of exploring theory which have nothing to do with anything observed.

Models used as analogies

Analogical applicability comes from the flexibility of the human mind in interpreting accounts in terms of the different situations. When we encounter a new situation, the account is mapped onto it – the account being used as an analogy for understanding this situation. Such accounts are typically in the form of a narrative, but a model can also be used as an analogy (which is the case we are concerned with here). The flexibility with which this mapping can be constructed means that such an account can be related to a wide range of phenomena. Such analogical mapping can lead to an impression that the account has a wide range of applicability. Analogies are a powerful tool for thinking since it may give us some insights into otherwise novel situations. There are arguments that analogical thinking is a fundamental aspect of human thought (Hofstadter 1995) and language (Lakoff 2008). We can construct and use analogical mappings so effortlessly that they seem natural to us. The key thing about analogical thinking is that the mapping from the analogy to the situation to which it is applied is re-invented each time – there is no fixed relationship between the analogy and what it might be applied to. We are so good at doing this that we may not be aware of how different the constructed mapping is each time. However, its flexibility comes at a cost, namely that because there is no well-defined relationship with what it applies to, the mapping tends to be more intuitive than precise. An analogy can give insights but analogical reasoning suggests rather than establishes anything reliably and you cannot empirically test it (since analogical mappings can be adjusted to avoid falsification). Such “ways of thinking” might be helpful, but equally might be misleading [note 1].

Just because the content of an analogy might be expressed formally does not change any of this (Edmonds 2018), in fact formally expressed analogies might give the impression of being applicable, but often are only related to anything observed via ideas – the model relates to some ideas, and the ideas relate to reality (Edmonds 2000). Using models as analogies is a valid use of models but this is not an empirically reliable one (Edmonds et al. 2019). Arnold (2013) makes a powerful argument that many of the more abstract simulation models are of this variety and simply not relatable to empirically observed cases and data at all – although these give the illusion of wide applicability, that applicability is not empirical. In physics the ways of thinking about atomic or subatomic entities have changed over time whilst the mathematically-expressed, empirically-relevant models have not (Hartman 1997). Although Thompson (2022) concentrates on mathematically formulated models, she also distinguishes between well-validated empirical models and those that just encapsulate the expertise/opinion of the modeller. She gives some detailed examples of where the latter kind had disproportionate influence, beyond that of other expertise, just because it was in the form of a model (e.g. the economic impact of climate change).

An example of an analogical model is described in Axelrod (1984) – a formalised tournament where algorithmically-expressed strategies are pitted against each other, playing the iterated prisoner’s dilemma game. It is shown how the ‘tit for tat’ strategy can survive against many other mixes of strategies (static or evolving). In the book, the purpose of the model is to suggest a new way of thinking about the evolution of cooperation. The book claims the idea ‘explains’ many observed phenomena, but this in an analogical manner – no precise relationship with any observed measurements is described. There is no validation of the model here or in the more academic paper that described these results (Axelrod & Hamilton 1981).

Of course, researchers do not usually call their models “analogies” or “analogical” explicitly but tend to use other phrasings that imply a greater importance. An exception is Epstein (2008) where it is explicitly listed as one of the 15 modelling purposes, other than prediction, that he discusses. Here he says such models are “…more than beautiful testaments to the unifying power of models: they are headlights in dark unexplored territory.” (ibid.) thus suggesting their use in thinking about phenomena where we do not already have reliable empirical models. Anything that helps us think about such phenomena could be useful, but that does not mean they are at all reliable. As Herbert Simon said: “Metaphor and analogy can be helpful, or they can be misleading. ” (Simon 1968, p. 467).

Another purpose listed in Epstein (2008) is to “Illuminate core dynamics”. After raising the old chestnut that “All models are wrong”, he goes on to justify them on the grounds that “…they capture qualitative behaviors of overarching interest”. This is fine if the models are, in fact, known to be useful as more than vague analogies [Note 2] – that they do, in some sense, approximate observed phenomena – but this is not the case with novel models that have not been empirically tested. This phrase is more insidious, because it implies that the dynamics that have been illuminated by the model are “core” – some kind of approximation of what is important about the phenomena, allowing for future elaborations to refine the representation. This implies a process where an initially rough idea is iteratively improved. However, this is premature because we do not know if what has been abstracted away in the abstract model was essential to the dynamics of the target phenomena or not without empirical testing – this is just assumed or asserted based on the intuitions of the modeller.

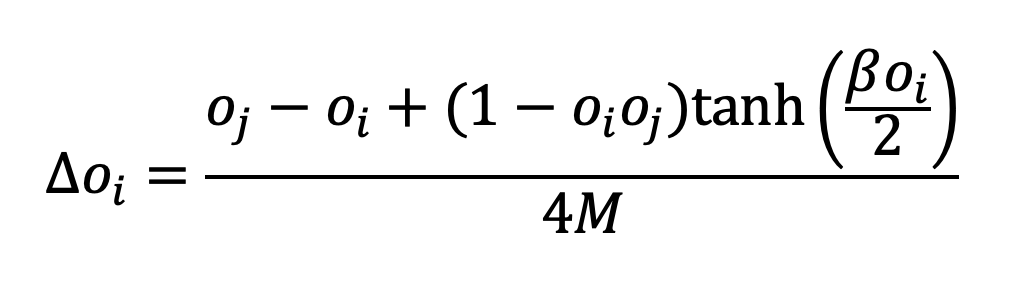

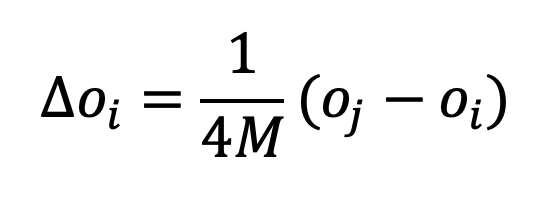

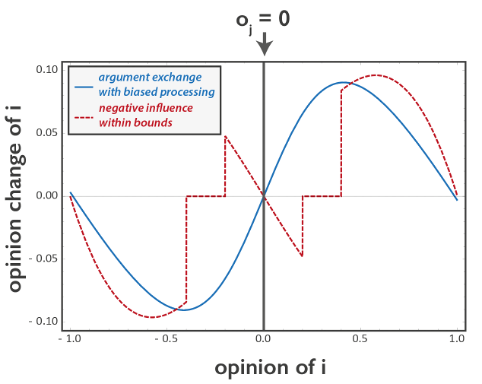

This idea of the “core dynamics” leads to some paradoxical situations – where a set of competing models are all deemed to be core. Indeed, the literature has shown how the same phenomenon can be modelled in many contrasting ways. For instance, political polarisation has been modelled through models with mechanisms for repulsion, bounded confidence, reinforcement, or even just random fluctuations, to name a few (Flache et al., 2017; Banisch & Olbrich 2019; Carpentras et al. 2022). However, it is likely that only a few of them contribute substantially to the political polarisation we observe in the real world, and so that all the others are not a real “core dynamic” but until we have more empirical work we do not know which are core and which not.

A related problem with analogical models is that, even when relying on parsimony principles [Note 3], it is not possible to decide which model is better. This aspect, combined with the constant production of new models, can makes the relevant literature increasingly difficult to navigate as models proliferate without any empirical selection, especially for researchers new to ABM. Furthermore, most analogical models define their object of study in an imprecise manner so that it is hard to evaluate whether they are even intended to capture element of any particular observed situation. For example, opinion dynamics models rarely define the type of interaction they represent (e.g. in person vs online) or even what an opinion is. This has led to cases where even knowledge of facts has been studied as “opinions” (e.g. Chacoma & Zanette, 2015).

In summary, analogical models can be a useful tool to start thinking about complex phenomena. However, the danger with them is that they give an impression of progress but result in more confusion than clarity, possibly slowing down scientific progress. Once one has some possible insights, one needs to confront these with empirical data to determine which are worth further investigation.

Models that relate directly to empirical data

An empirical model, in contrast, has a well-defined way of mapping to the phenomena it represents. For example, the variables of the gas laws (volume, temperature and pressure) are measured using standard methods developed over a long period of time, one does not invent a new way of doing this each time the laws are applied. In this case, the ways of measuring these properties have developed alongside the mathematical models of the laws so that these work reliably under broad (and well known) conditions and cannot be adjusted at the whim of a modeller. Empirical generality comes from when a model applies reliably to many different situations – in the case of the gas laws, to a wide range of materials in gaseous form to a high degree of accuracy.

Empirical models can be used for different purposes, including: prediction, explanation and description (Edmonds et al. 2019). Each of these uses how the model is mapped to empirical data in different ways, to reflect these purposes. With a descriptive model the mapping is one-way from empirical data to the model to justify the different parts. In a predictive model, the initial model setup is determined from known data and the model is then run to get its results. These results are then mapped back to what we might expect as a prediction, which can be later compared to empirically measured values to check the model’s validity. An explanatory model supports a complex explanation of some known outcomes in terms of a set of processes, structures and parameter values. When it is shown that the outcomes of such a model sufficiently match those from the observed data – the model represents a complex chain of causation that would result in that data in terms of the processes, structures and parameter values it comprised. It thus supports an explanation in terms of the model and its input of what was observed. In each of these three cases the mapping from empirical data to the model happens in a different order and maybe in a different direction, however they all depend upon the mapping being well defined.

Cartwright (1983), studying how physics works, distinguished between explanatory and phenomenological laws – the former explains but does not necessary relate exactly to empirical data (such as when we fit a line to data using regression), whilst the latter fits the data but does not necessarily explain (like the gas laws). Thus the jobs of theoretical explanation and empirical prediction are done by different models or theories (often calling the explanatory version “theory” and the empirical versions “models”). However, in physics the relationship between the two is, itself, examined so that the “bridging laws” between them are well understood, especially in formal terms. In this case, we attribute reliable empirical meaning to the explanatory theories to the extent that the connection to the data is precise, even though it is done via the intermediary of an “phenomenological” model because both mappings (explanatory↔phenomenological and phenomenological↔empirical data) are precise and well established. The point is that the total mapping from model or theory to empirical data is not subject to interpretation or post-hoc adjustment to improve its fit.

ABMs are often quite complicated and require many parameters or other initialising input to be specified before they can be run. If some of these are not empirically determinable (even in principle) then these might be guessed at using a process of “calibration”, that is searching the space of possible initialisations for some values for which some measured outcomes of the results match other empirical data. If the model has been separately shown to be empirically reliable then one could do such a calibration to suggest what these input values might have been. Such a process might establish that the model captures a possible explanation of the fitted outcomes (in terms of the model plus those backward-inferred input values), but this is not a very strong relationship, since many models are very flexible and so could fit a wide range of possible outcomes. The reliability of such a suggested explanation, supported by the model, is only relative to (a) the empirical reliability of any theory or other assumptions the model is built upon (b) how flexibly the model outcomes can be adjusted to fit the target data and (c) how precisely the choice of outcome measures and fit are. Thus, calibration does not provide strong evidence of the empirical adequacy of an ABM and any explanation supported by such a procedure is only relative to the ‘wiggle room’ afforded by free parameters and unknown input data as well as any assumptions used in the making of the model. However, empirical calibration is better than none and may empirically fix the context in which theoretical exploration occurs – showing that the model is, at least, potentially applicable to the case being considered [Note 4].

An example of a model that is strongly grounded in empirical data is the “538” model of the US electoral college for presidential elections (Silver 2012). This is not an ABM but more like a micro-simulation. It aggregates the uncertainty from polling data to make probabilistic predictions about what this means for the outcomes. The structure of the model comes directly from the rules of the electoral college, the inputs are directly derived from the polling data and it makes predictions about the results that can be independently checked. It does a very specific, but useful job, in translating the uncertainty of the polling data into the uncertainty about the outcome.

Why this matters

If people did not confuse the analogical and empirical cases, there would not be a problem. However, researchers seem to suffer from a variety of “Kuhnian Spectacles” (Kuhn 1962) – namely that because they view their target systems through an analogical model, they tend to think that this is how that system actually is – i.e. that the model has not just analogical but also empirical applicability. This is understandable, we use many layers of analogy to navigate our world and in many every-day cases it is practical to conflate our models with the reality we deal with (when they are very reliable). However, people who claim to be scientists are under an obligation to be more cautious and precise than this, since others might wish to rely upon our theories and models (this is, after all, why they support us in our privileged position). However, such caution is not always followed. There are cases where modellers declare their enterprise a success even after a long period without any empirical backing, making a variety of excuses instead of coming clean about this lack (Arnold 2015).

Another fundamental aspect is that agent-based models can be very interdisciplinary and, because of that, they can be used also by researchers in different fields. However, many fields do not consider models as simple analogies, especially when they provide precise mathematical relationship among variables. This can easily result in confusions where the analogical applicability of ABMs is interpreted as empirical in another field.

Of course, we may be hopeful that, sometime in the future, our vague or abstract analogical model maybe developed into something with proven empirical abilities, but we should not suggest such empirical abilities until these have been established. Furthermore, we should be particularly careful to ensure that non-modellers understand that this possibility is only a hope and not imply anything otherwise (e.g. imply that it is likely to have empirical validity). However, we suspect that in many cases this confusion goes beyond optimistic anticipation and that some modellers conflate analogical with empirical applicability, assuming that their model is basically right just because it seems that way to them. This is what we call “delusional generality” – that a researcher is under the impression that their model has a wide applicability (or potentially wide applicability) due to the attractiveness of the analogy it presents. In other words, unaware of the unconscious process of re-inventing the mapping to each target system, they imagine (without further justification) that it has some reliable empirical (or potentially empirical) generality at its core [Note 5].

Such confusion can have severe real-world consequences if a model with only analogical validity is assumed to also have some empirical reliability. Thompson (2022) discusses how abstract economic models of the cost of future climate change did affect the debate about the need for prevention and mitigation, even though they had no empirical validity. However, agent-based modellers have also made the same mistake, with a slew of completely unvalidated models about COVID affecting public debate about policy (Squazzoni et al 2021).

Conclusion

All of the above discussion raises the question of how we might achieve reliable models with even a moderate level of empirical generality in the social sciences. This is a tricky question of scientific strategy, which we are not going to answer here [Note 6]. However, we question whether the approach of making “heroic” jumps from phenomena to abstract non-empirical models on the sole basis of its plausibility to its authors will be a productive route when the target is complex phenomena, such as socio-cognitive systems (Dignum, Edmonds and Carpentras 2022). Certainly, that route has not yet been empirically demonstrated.

Whatever the best strategy is, there is a lot of theoretical modelling in the field of social simulation that assumes or implies that it is the precursor for empirical applicability and not a lot of critique about the extent of empirical success achieved. The assumption seems to be that abstract theory is the way to make progress understanding social phenomena but, as we argue here, this is largely wishful thinking – the hope that such models will turn out to have empirical generality being a delusion. Furthermore, this approach has substantive deleterious effects in terms of encouraging an explosion of analogical models without any process of selection (Edmonds 2010). It seems that the ‘famine’ of theory about social phenomena with any significant level of generality is so severe, that many seem to give credence to models they might otherwise reject – constructing their understanding using models built on sand.

Notes

1. There is some debate about the extent to which analogical reasoning works, what kind of insights it results in and under what circumstances (Hofstede 1995). However, all we need for our purposes is that: (a) it does not reliably produce knowledge, (b) the human mind is exceptionally good at ‘fitting’ analogies to new situations (adjusting the mapping to make it ‘work’ somehow) and (c) due to this ability analogies can be far more convincing that the analogical reasoning warrants.

2. In pattern-oriented modelling (Grimm & al 2005) models are related to empirical evidence in a qualitative (pattern-based) manner, for example to some properties of a distribution of numeric outcomes. In this kind of modelling, a precise numerical correspondence is replaced by a set of qualitative correspondences in many different dimensions. In this the empirical relevance of a model is established on the basis that it is too hard to simultaneously fit a model to evidence in this way, thus ruling that out as a source of its correspondence with that evidence.

3. So-called “parsimony principles” are a very unreliable manner of evaluating competing theories on grounds other than convenience or that of using limited data to justify the values of parameters (Edmonds 2007).

4. In many models a vague argument for its plausibility is often all that is described to show that it is applicable to the cases being discussed. At least calibration demonstrates its empirical applicability, rather than simply assuming it.

5. We are applying the principle of charity here, assuming that such conflations are innocent and not deliberate. However, there is increasing pressure from funding agencies to demonstrate ‘real life relevance’ so some of these apparent confusions might be more like ‘spin’ – trying to give an impression of empirical relevance even when this is merely an aspiration, in order to suggest that their model has more significant than they have reliably established.

6. This has been discussed elsewhere, e.g. (Moss & Edmonds 2005).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all those we have discussed these issues with, including Scott Moss (who was talking about these kinds of issue more than 30 years ago), Eckhart Arnold (who made many useful comments and whose careful examination of the lack of empirical success of some families of model demonstrates our mostly abstract arguments), Sven Banisch and other members of the ESSA special interest group on “Strongly Empirical Modelling”.

References

Arnold, E. (2013). Simulation models of the evolution of cooperation as proofs of logical possibilities. How useful are they? Ethics & Politics, XV(2), pp. 101-138. https://philpapers.org/archive/ARNSMO.pdf

Arnold, E. (2015) How Models Fail – A Critical Look at the History of Computer Simulations of the Evolution of Cooperation. In Misselhorn, C. (Ed.): Collective Agency and Cooperation in Natural and Artificial Systems. Explanation, Implementation and Simulation, Philosophical Studies Series, Springer, pp. 261-279. https://eckhartarnold.de/papers/2015_How_Models_Fail

Axelrod, R. (1984) The Evolution of Cooperation, Basic Books.

Axelrod, R. & Hamilton, W.D. (1981) The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211, 1390-1396. https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.7466396

Banisch, S., & Olbrich, E. (2019). Opinion polarization by learning from social feedback. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 43(2), 76-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.2018.1517761

Carpentras, D., Maher, P. J., O’Reilly, C., & Quayle, M. (2022). Deriving An Opinion Dynamics Model From Experimental Data. Journal of Artificial Societies & Social Simulation, 25(4).http://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.4947

Cartwright, N. (1983) How the Laws of Physics Lie. Oxford University Press.

Chacoma, A. & Zanette, D. H. (2015). Opinion formation by social influence: From experiments to modelling. PloS ONE, 10(10), e0140406.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140406

Dignum, F., Edmonds, B. and Carpentras, D. (2022) Socio-Cognitive Systems – A Position Statement. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 2nd Apr 2022. https://rofasss.org/2022/04/02/scs

Edmonds, B. (2000). The Use of Models – making MABS actually work. In. S. Moss and P. Davidsson. Multi Agent Based Simulation. Berlin, Springer-Verlag. 1979: 15-32. http://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-44561-7_2

Edmonds, B. (2007) Simplicity is Not Truth-Indicative. In Gershenson, C.et al. (eds.) Philosophy and Complexity. World Scientific, pp. 65-80.

Edmonds, B. (2010) Bootstrapping Knowledge About Social Phenomena Using Simulation Models. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 13(1), 8. http://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.1523

Edmonds, B. (2018) The “formalist fallacy”. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 11th June 2018. https://rofasss.org/2018/07/20/be/

Edmonds, B., le Page, C., Bithell, M., Chattoe-Brown, E., Grimm, V., Meyer, R., Montañola-Sales, C., Ormerod, P., Root H. & Squazzoni. F. (2019) Different Modelling Purposes. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 22(3):6. http://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.3993

Epstein, J. M. (2008). Why Model?. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 11(4),12. https://www.jasss.org/11/4/12.html

Flache, A., Mäs, M., Feliciani, T., Chattoe-Brown, E., Deffuant, G., Huet, S. & Lorenz, J. (2017). Models of social influence: Towards the next frontiers. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 20(4), 2. http://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.4298

Grimm, V., Revilla, E., Berger, U., Jeltsch, F., Mooij, W.M., Railsback, S.F., et al. (2005). Pattern-oriented modeling of agent-based complex systems: lessons from ecology. Science, 310 (5750), 987–991. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3842807

Hartman, S. (1997) Modelling and the Aims of Science. 20th International Wittgenstein Symposium, Kirchberg am Weshsel.

Hofstadter, D. (1995) Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies. Basic Books.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. (2008). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. University of Chicago Press.

Merton, R.K. (1968). On the Sociological Theories of the Middle Range. In Classical Sociological Theory, Calhoun, C., Gerteis, J., Moody, J., Pfaff, S. and Virk, I. (Eds), Blackwell, pp. 449–459.

Meyer, R. & Edmonds, B. (2023). The Importance of Dynamic Networks Within a Model of Politics. In: Squazzoni, F. (eds) Advances in Social Simulation. ESSA 2022. Springer Proceedings in Complexity. Springer. (Earlier, open access, version at: https://cfpm.org/discussionpapers/292)

Moss, S. and Edmonds, B. (2005). Towards Good Social Science. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 8(4), 13. https://www.jasss.org/8/4/13.html

Squazzoni, F. et al. (2020) ‘Computational Models That Matter During a Global Pandemic Outbreak: A Call to Action’ Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 23(2):10. http://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.4298

Silver, N, (2012) The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail – But Some Don’t. Penguin.

Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American philosophical society, 106(6), 467-482.https://www.jstor.org/stable/985254

Thompson, E. (2022). Escape from Model Land: How mathematical models can lead us astray and what we can do about it. Basic Books.

Wartofsky, M. W. (1979). The model muddle: Proposals for an immodest realism. In Models (pp. 1-11). Springer, Dordrecht.

Zeigler, B. P. (1976). Theory of Modeling and Simulation. Wiley Interscience, New York.

Edmonds, B., Carpentras, D., Roxburgh, N., Chattoe-Brown, E. and Polhill, G. (2024) Delusional Generality – how models can give a false impression of their applicability even when they lack any empirical foundation. Review of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 7 May 2024. https://rofasss.org/2024/05/06/delusional-generality

© The authors under the Creative Commons’ Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND) Licence (v4.0)